La Coquille. Conversation entre Issa Samb et Antje Majewski. Dakar 2010, 2010

Conversation with the artist and philosopher Issa Samb in his yard in Dakar. Issa Samb talks about our responsibility to help objects move in the world, while respecting their history and origin, even in the tiniest object made in China. The charge that objects carry derives ultimately from the same force that also fills us.

“Each leaf that may fall in this garden here, and that passes from the situation of being a natural leaf to becoming an object, moving from here to there, adopts a position, which participates in the definition of the whole ensemble in front of us. And beyond this location, the whole peninsula of Dakar, and beyond the peninsula the whole continent, and beyond the continent the whole world. It is not a question of interactivity, neither is it even a question of interference. It is a question of the inter-relationships of living things…”

(Issa Samb)

In the second half of the film Issa Samb unexpectantly tells Antje Majewski to listen to a big shell that she had brought with her, and guides her into a trance in which she describes the inside of the sea and hears a voice singing in the shell.

I bought the large shell[1] in Dakar, Senegal seven years ago. I can’t remember where it was exactly that I found it—but I believe it was near the Place de l’Indépendance, just before I left the country. We met a young woman in a shared taxi from St. Louis to Dakar, and she invited us to visit her family. Her elderly father was a marabout, an Islamic scholar who was consulted as a mediator to God. He could pray for you vicariously, give advice and also help you find more luck. Nanette had inherited this gift, as had her brother, a rap musician. His three families lived in a complex of houses surrounding a courtyard, on a quiet, unpaved road. I flew back to Berlin with the shell in my suitcase, along with the vague idea that I would have to return to Dakar, find this road again and shoot a film there with Nanette. This film should be called La collectioneuse. A girl should be assembling things on a shelf in her room in Dakar, things that I would find in the port area in Bremen, Germany and wanted to send on a journey to Africa by ship.

Instead I myself travelled back to Senegal in the spring of 2010 and brought my objects with me, with the intention of maybe showing them to a marabout. I had the urgent feeling that now I had to go to Dakar, had looked for different ways to do so and eventually became acquainted with Clémentine Deliss, who also wanted to go to Dakar. I packed my old camera and a small microphone. Clémentine was certain that I should meet her longtime friends Issa Samb and El Hadji Sy, members of the Laboratoire Agit’Art, and ask them about my objects.

El Hadji Sy came into my hotel room, saw the objects spread on the table and said to me, “Ce sont les choses mêmes qui t’ont ramené ici.” (“It’s the things themselves that led you here.”) The next day, we went to visit Issa Samb. Issa lives in a space full of things either standing around or hanging on strings. Friends and visitors sit down with him under a huge tree, which stands in the middle.

After sitting there in silence for a few days, just listening to the conversations from the sidelines and photographing all the objects, I gave up hope. Issa did not speak to me. But then Abdou Bâ, a friend of his, said to me: “Come on Friday morning.” I came to the space and set up my camera, and Issa Samb sat down and we had a conversation that became very important to me.

Issa told me that we should not deprive things of their history, because that would negate the history of all the hands that made them or through which they had passed. Besides their use, they also carry something else within them that is the same as that which we carry within us, and that we have to respect even in the smallest, most breakable thing from China: a force that fills not only people, animals and plants, but also objects. Every action, every movement of things and people changes the world order, and it is our responsibility to help objects with their movements so that they can participate in the self-realization of the world.

Finally I put the shell, the meteorite and the Buddha-hand on the table. But it wasn’t Issa who explained my things to me: I had to do it myself. Abdou said, “I’ll help you,” took over the camera and filmed the second half, most of all me. Issa led me deeper and deeper into an inner seascape, until I finally had to admit–against my will–that in truth I no longer saw the sea, but heard a woman’s voice singing a single note, clear and pure. Issa made a motion and I fell into a trance. That all came to me quite unexpectedly. The next day, and even in the next few months, I was exhausted, as if emptied. While the voice in the shell was sweet and loving, the energy conveyed to me in the trance was very strong but also cold, even icy.

Two days later, I filmed another interview with El Hadji Sy in which we talk about reflections, hinges, and the gaze. In this conversation, I mention a door by Marcel Duchamp that is mounted between two doorways, and compare the hinge to my trip to Africa, which also represents a hinge. With doors like these, it is not clear which side is the front and which is the back, just as in my interview with Issa Samb, I cannot say whether the second half of the conversation (during which something spoke through me) is the reverse side of the first part where Issa was speaking. I have blacked out the trance part in the film because I don’t want to show it. It doesn’t seem right to me. I know what was conveyed to me: but I have no words, no story to tell. I can’t say anything about it. Even Issa has not told me whose voice it was that I heard in the shell, or what was transmitted to me. Once I reawakened, he stood up and continued sweeping the yard. I later asked Abdou if it couldn’t have been N’doep–but he said no: first of all I wasn’t ill, second, there were none of the ceremonies associated with it. Supposedly there had been a special relationship between Issa and myself, one that he did not understand, either; but in this case whatever had happened was good–“like an assisted birth”.

The Lebou, to whom Issa Samb also belongs, are traditionally fishermen and very closely tied to the sea. There is not only one deity of the sea, but different ones for different places along the coast, all of which have different names and can be male or female. The Lebou conduct trance ceremonies called N’doep, which are primarily meant to lead the mentally ill back into the community. N’doep works by involving the entire village, which organizes a celebration over several days in the hope of leading the afflicted back to his community. Mental illness is seen as the result of broken ties: the person becomes a stranger in his own family, his village – or goes crazy after he moved to town, because he has been estranged from his roots. In order for him to be cured, the disease must be violently broken once more. The afflicted, for instance, lies under blankets next to a sacrificial animal. Spirits are called to ward off whatever has taken hold of him.

On a trip to Senegal, the photographer Leonore Mau and writer Hubert Fichte investigated the practice of psychiatry in Fann, where Western medicine was applied along with the traditional methods of N’doep.[2] Laboratoire Agit’Art also participated in attempts to find a new form of psychiatry that uses African knowledge. For Fichte and Mau, their travels to Africa were also an attempt to establish a link between the Afro-American religions and the Brazilian Cadomblé, which they had been studying closely, in the hope of reconnecting them with their origins in West Africa. Though neither allowed themselves to be initiated, they did take on an important task: they brought the chants of the Casa das Minas from Brazil back to the place from which they came, to the court of the king of Abomé.[3] The Casa das Minas priestesses wanted to know if these chants were still correct after 500 years of exile in Brazil. They gave Fichte and Mau a glass bead necklace as an identifying sign, which was inspected pearl-by-pearl in Abomé by King Laganfin Glele Joseph, who acknowledged it. After Hubert Fichte’s untimely death, Leonore Mau had to return this necklace to Brazil alone.

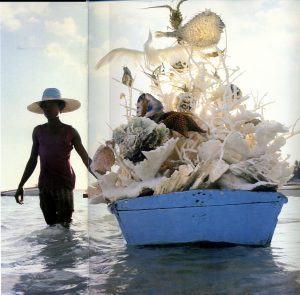

Mau’s photograph from the book Petersilie[4] shows a boat heaped and covered with shells, like a freight shipment for Yemanja, sea and love goddess to the Afro-American religions. Gifts were taken into the sea in her honour, pushed into the water on boats. Yet the caption reads: “A souvenir merchant from Boca Chica has constructed a magic ship for the tourists.”

There is a passage in the book Forschungsbericht[5] where Hubert Fichte describes a failure. They had travelled to Belize and had tried to find stories there, secret recipes for trance drinks. But they were fooled, and not allowed into the rites. Fichte found not a single opportunity for homosexual encounters. They simply could go no further. Then Fichte suggested to Mau that she photograph white eggs against a white wall “for practice”. Mau was insulted and said she didn’t practice. She was not interested in purely formal gimmicks, or proof of craft and skill.

Leonore Mau

Fata Morgana, after 1999