Freisler, 2010-11

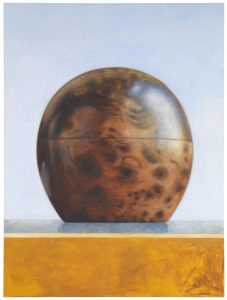

I bought the black ball in Warsaw in about 2004; the glass eyes were movie props and had originally come from the practice of a Berlin ophthalmologist who inserted glass eyes; and the container of Moroccan root wood is from a Paris flea market. It is, in other words, the only object that actually consists of several objects of different origin. In my painting you see only the closed container. “The small black pot with the ball, that’s the magic. You open it, and inside is the mystery.” (Alejandro Jodorowsky)

The Pot made of Fragrant Wood.

Contains one Black Ball or Two Glass Eyes, 2010

It turned out that the ball behaved in a similar way to the wandering meteorite; both wanted to go from one place to another, show up here and there and pass through several hands. The ball wanted to move or transport times and spaces. It also wanted to turn into an egg, and then into apples, that multiply.

I first used the black ball for a performance for the Séminaire à la Campagne (2010). On the flight home to Berlin I was talking with Agnieszka Polska about my performance. She said, “It reminds me of a Polish conceptual artist from the 60s,” and I said, “Paweł Freisler?” We were both astonished because as an artist, Freisler is a legend known only to few. He vanished about 20 years ago, lived “in Norway” and supposedly worked in his garden “with apples”, as I had heard from friends. All this was part of his work, which had long consisted in not showing any material artworks, but circulating legends instead.[1]

In 1968, Freisler had begun working with an egg that he had a precision instruments factory cast in steel on 14th August 1969, for the Laboratorium Sztuki Galerii EL. He initially called it Stalowy wzór jajka kurzego (Standard Chicken Egg Made of Steel). Shortly thereafter, this became Imperialny wzór jajka kurzego (Imperial Standard for a Chicken Egg), and today it is usually called Stalowe jajo (Steel Egg), or Das Ei or The Egg, respectively. Because the story of The Egg is still ongoing, its title is still “in the making” (Paweł Freisler). The Egg was not exhibited, but entrusted to people. Among others, the popular Polish actor Wiesław Gołas carried it around with him from February 1970 to February 1971 and had to show it upon demand; and it was brought to Paris, where Jean-Paul Belmondo took it for a cruise on the hood of his car.[2]

On the flight home, Agnieszka and I realized that we both definitely wanted to visit Freisler. That summer I ran–together with Juliane Solmsdorf, Dirk Peuker and Magdalena Magiera–a large, empty art space at the base of the television tower in Berlin. At Splace, we invited artist friends to arrange a total of twelve exhibitions.[3] I invited Agnieszka to do a Freisler exhibition with me. We tried to get in touch with him, but he did not reply.

Finally, I wrote the text for a performance in which we both travel to Sweden and steal his egg by sending little machines into his garden, where it is buried. The machines burrow into the ground and bring us The Egg, which we then take to Berlin and glue underneath one of the tables in the rotating restaurant at the top of the television tower.

What we actually did was water an imaginary garden on the concrete floor at Splace in the middle of Berlin, using water we had brought from a fire hydrant hidden in the ground at Alexanderplatz. I scattered seeds made out of little metal balls that the visitors could then take with them.

We also screened Agnieszka’s Film Ogrod. Here you are led into Freisler’s garden, where his Egg can be found resting amongst the plants. A voice over, from a man of whom we only see a hand, explains how carefully these rare flowers are cultivated, cites their complicated names and explains to us the sprinkler system and the precautions taken against pests.

Agnieszka Polska, Ogrod, 2009

When I was preparing the exhibition The World of Gimel, I asked the Kunsthaus Graz to send a Freisler a formal request for The Egg and to our great surprise, he agreed. I wrote to him about happy I was about it and sent him my text. Thus began an e-mail exchange that also involved many others-an exchange extensive enough to be a book on its own. We are only able to print excerpts here.

Freisler named Łukasz Ronduda as the one who should tell the story of The Egg in the context of my exhibition. He said Ronduda would be The Professor, an artwork that Paweł Freisler had developed long ago.

Łukasz Ronduda as “The Professor”

So Freisler entrusted the telling of his legend to Łukasz Ronduda, but The Egg itself to me, as his deposit in a bank: “to put The Egg into the safe of a Bank is to accept the system … and vice versa, the system must accept The Egg, its otherness”: “One might as well form their Own bank” using The Egg as a deposit that could give credit (“credit of trust”).

The credit lending and multiplication of The Egg from the unconscious began in a very unexpected way. Without knowing about Freisler, Simon Starling and Rasmus Nielsen (Superflex) gave Adam Budak a proposal for the jubilee year. They wanted to produce nine different-sized eggs out of steel; The Eggs would wander as “aliens” throughout the various departments, where they would come into direct contact with the objects in that section. This would create new stories–one of these was even to be carried around by one of the curators, just like Freisler’s The Egg from forty years earlier. These eggs were to be called not “Standard” but “Super” eggs and were based on a design by Piet Hein. They are flattened at both ends, so they can stand on their own.

I sent Freisler an e-mail telling him about this new development. Freisler did not reply. The following spring, Kunsthaus Graz asked him to send them The Egg because the first Super Eggs were finished and we very much wanted to bring about a meeting of The Eggs. After a few more conceptual complications relating to the insured value (the “maximum possible”), and the address for the loan agreement (he gave us two house numbers to choose from on the same street: No. 24b and 23b – we chose the odd number) The Egg finally arrived in Graz, wrapped in a thick, grey beard.

Paweł Freisler, Stalowe Jajo, 1964

There, “Super Eggs” were “laid” in the Zeughaus and in the Schloss Eggenberg Archaeology Museum. The heaviest, which weighed nearly a ton, was taken into the Measuring the World exhibition at Kunsthaus Graz and remains in the same place for The World of Gimel.

Simon Starling and Rasmus Nielsen, Super Egg, 2011

and Paweł Freisler, The Egg, 1964

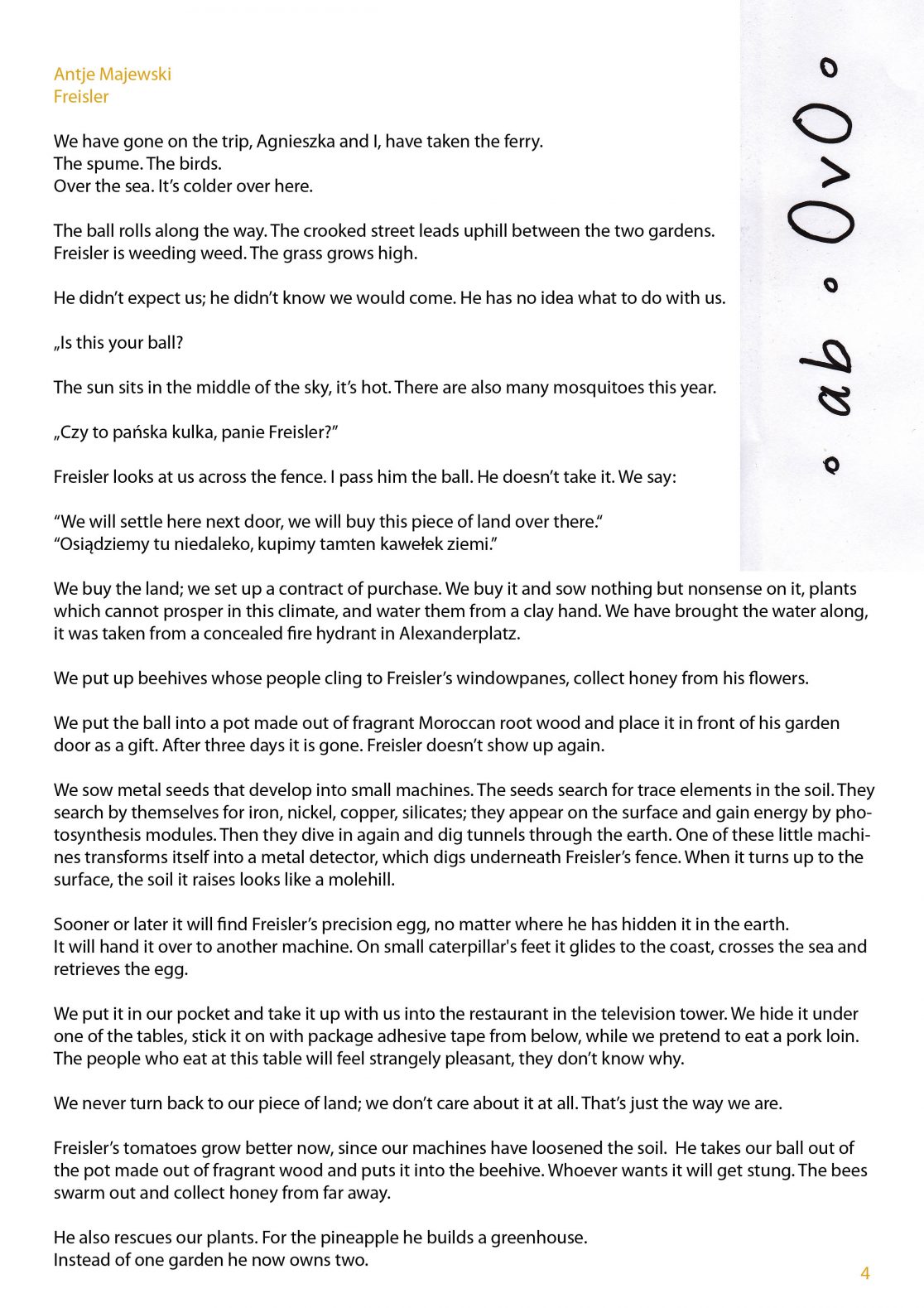

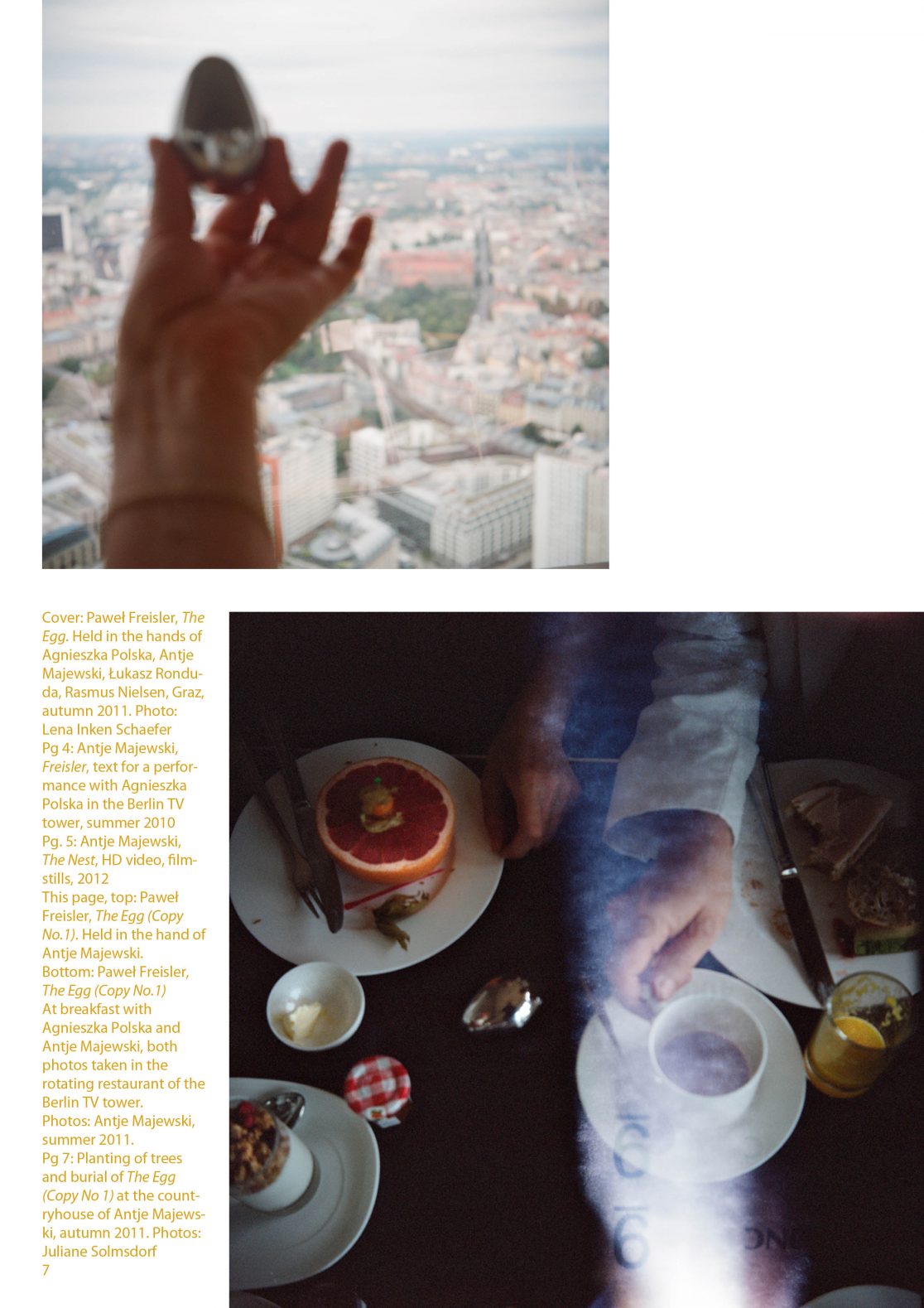

But how should The Egg be shown in the exhibition? I myself would have preferred to “steal” it and bring it to the TV tower with Agnieszka Polska. Freisler answered that the loan agreement had been made with the Kunsthaus Graz, but I was welcome to make a copy of The Egg. We commissioned the same company that had also cast the “Super Eggs”, with a copy that received the number 1. The original was on view in the exhibition, in a bank deposit box in a high security display case, the same one that was used for the Coin de chasteté by Marcel Duchamp. The copy was sent to me in Berlin. Agnieszka Polska and I went to eat at the rotating restaurant in the TV tower (we had pork); and we drove around with Das Ei (Kopie Nr. 1) a few times so that the city could reflect in it.[4]

The Egg (Copy No 1) at the TV tower

In the fall, I brought it to the countryside and threw a big celebration in which Das Ei (Kopie Nr. 1) was buried in the garden. At the party we ate large loaves of bread that look like children, sang and wore masks, and there were also fruit, dolls and other things. We planted apple trees, a nut tree, cherry trees, roses and many other plants. My friends helped me set up a small pyramid of stones over Das Ei (Kopie Nr. 1), so I’ll never forget exactly where it is.

Planting celebration in Himmelpfort

Today it has wandered off again, because someone else needed it more urgently then me. It is no longer in the garden but might return there one day.

The Eggs that had turned into little metal balls, like in the performance with Agnieszka Polska, or in the video Nest (2012), later transformed into apples in an ongoing collaboration with Paweł Freisler, in which not eggs, but apples keep multiplying. What had been put into the bank has given plentyful “credit of trust”. Thank you, Paweł