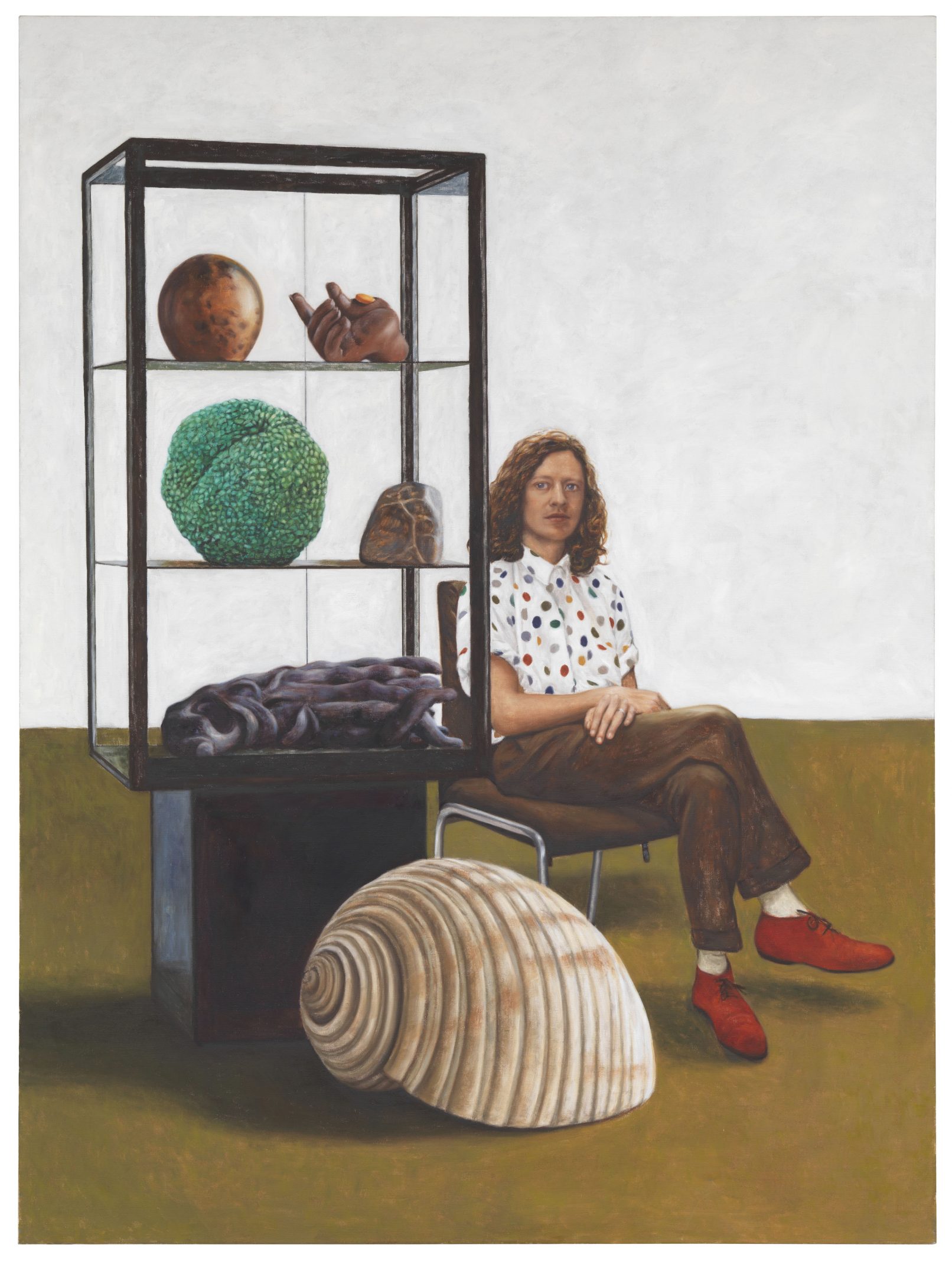

The Guardian of All Things that are the Case. The Eight Objects, 2009

The Aleph is stored in a writer’s basement. It contains all of the things in this world simultaneously.

“On the back part of the step, toward the right, I saw a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brilliance. At first I thought it was revolving; then I realised that this movement was an illusion created by the dizzying world it bounded. The Aleph’s diameter was probably little more than an inch, but all space was there, actual and undiminished.” In his short story The Aleph, Jorge Luis Borges follows a vertiginous list of far and near, past and present things; unrelated, they tumble one after another. “What my eyes beheld was simultaneous, but what I shall now write down will be successive, because language is successive.”

The Beta world contains not only the things of this planet, but also all those of all other possible planets and universes: the multiverse. It contains all pasts, all futures, and also the worlds in which there is no time or several times, likewise one-dimensional to x-dimensional spaces. Inevitably, it is not describable or representable. The World of Gimel inquires as to the relations of all these things to each other and to ourselves.

Two years ago, Peter Pakesch and Adam Budak asked me to think about the Universalmuseum Joanneum, which is turning 200 years old this year. It consists of a complex of individual museums, one of which is Kunsthaus Graz. The Universalmuseum was originally a project of the Enlightenment, founded for the Styrian population by the liberal Archduke Johann. The universality of this knowledge proved limited, both historically and regionally. The systematics of the natural scientific departments were redetermined, and their usage is now different. The mineralogy section, for instance, was originally intended to support the Styrian mining industry (Archduke Johann also helped to found a university for mining knowledge, now known as the “Montanuniversität”). Folklore collections were supposed to have a strengthening effect on the national spirit—these were associated with liberation movements and liberalism in the 19th century, though these days one would have a hard time understanding how a collection of traditional folk costumes could serve to form a national character. The departments were to be of practical use to the population, serving a purpose that is barely relevant today. Furthermore, compared to the analogy transformations1 of the Schloss Eggenberg, the differentiated, museum knowledge systems of today offer no symbolic knowledge about the world that can be translated into the everyday dealings with and relationships between people and their surroundings.

Presented in my universal museum, the painting of a glass vitrine and a museum guard, are seven objects that I bought on my travels; as to why exactly these seven should become my universals and what they meant, I didn’t know when I first started thinking about them three years ago. They are things of very little value; as proved by the expert’s report issued by the individual departments in Graz, none of them would be interesting for a museum collection.

Shortly thereafter, I received another invitation by basso in Berlin. Opening there, parallel to the opening of the prestigious “Neues Museum” in Berlin, was a very nice little museum with everything that a museum needs: guards, tour guides, online information, exhibition area, research, conservation… but in this museum, people also danced, made music and did performances, ate, talked and lived. All of these activities took place collaboratively and were also developed out of the moment. I painted The Guardian of all Things that are the Case for both exhibitions. Like a nutshell, the painting in the exhibition at basso already contained everything that will unfold in the big exhibition in Kunsthaus Graz.

In seven other paintings, the objects found in the vitrine are separately introduced or held by different individuals. There they are a nameless attribute, like in paintings of obscure Catholic saints, and they resemble Borges’ things. Each of these paintings found its place in an exhibition in which they came into contact with other artworks, artists and contexts.

Then I travelled to the places that the things came from: to Senegal, China, Poland and France. Everywhere I met people who helped me further. A few old artists became my teachers. I learned that you cannot rob things of their history, because they also always contain the history of the people who have held it in their hand before. Every one of my things that was “meaningless”, but fascinating to me, took me to a place in which it was alive and in a state of constant transformation. Many stories emerged around these few objects; they took me all over the world, and a network of friends, sages, askers and lovers tied together all by itself.

Now the things go to the dead site of the museum, the Joanneum in Graz, where the process of their mummification begins. Hopefully visitors will continue adding more and more knots to the net. The view I am describing is neither a simultaneous nor a successive one; it is rather like an ever-expanding net, the knots of which contain very simple truths. The simplest is the most difficult to say, but perhaps it can be encountered.

(Antje Majewski, 2011)