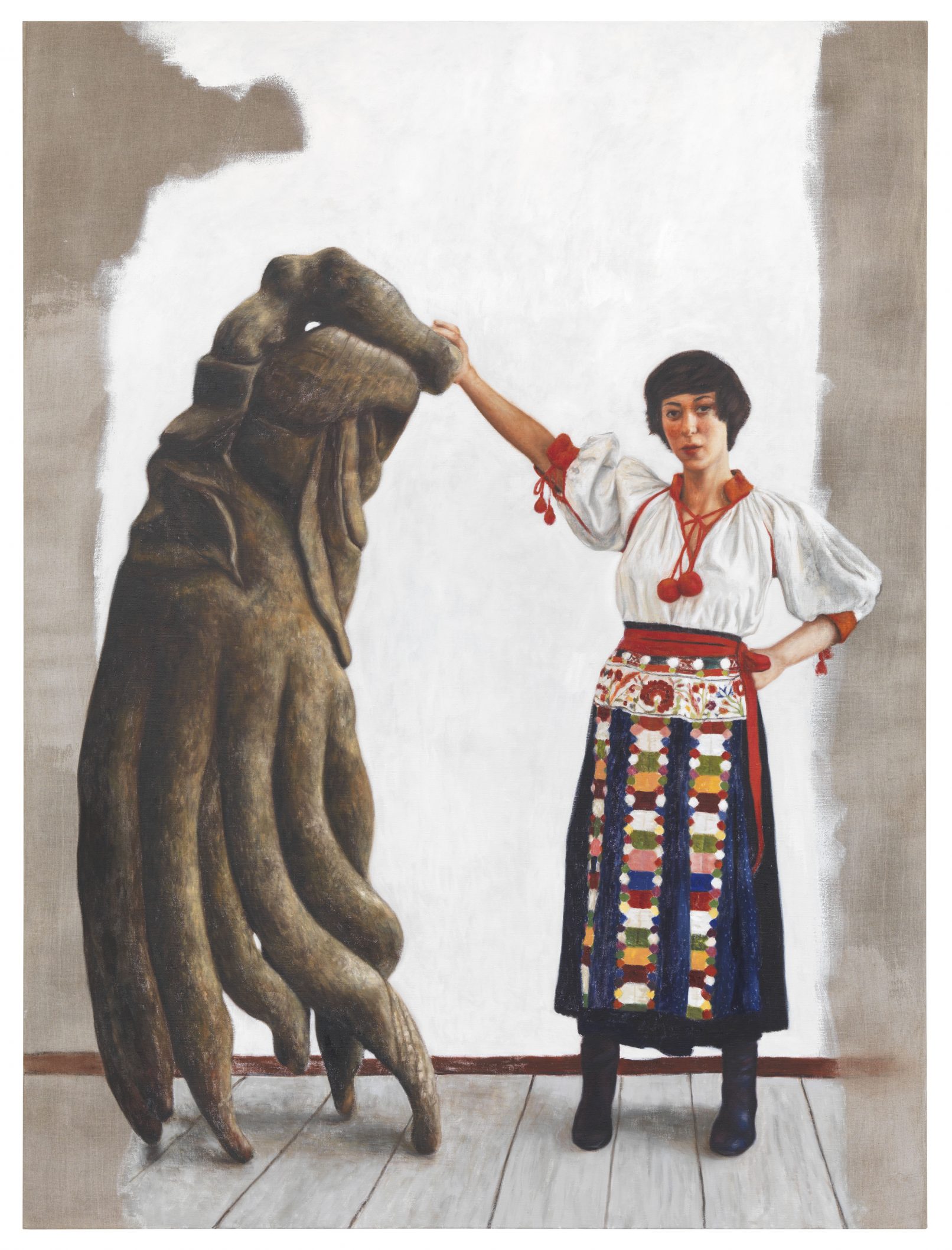

Miao Shan and the Buddha’s Hand, 2011

The Buddha’s hand is a “cultural socialized object” (Issa Samb) – so much so that if you don’t come from that culture, you don’t understand what it is. With the teapot hand, we might not know why it was made – but whenever I showed someone the hand and demonstrated how you can remove the little orange cap, whenever I filled it with water and poured from its index finger, then everyone understood the transformation of ‘hand” into “pot”. It was with the Buddha’s hand that the guesswork began. A jellyfish, a root, a creature, a what? It was only when I emailed photos of my objects to Shuxian Xu that I learned the name of the fruit and its history. The “fingered citron” or Buddha’s hand citron comes from southern China. The fruit blooms into slices at one end, all which are enclosed by the fruit’s peel. Thus it resembles a hand with many fingers.

Legend has it that the fragrant fruit was made by the hand of Princess Miao Shan. Her father, the king, did not want her to become a Buddhist and banished her into a garden. He then became very ill. Immortals appeared to Miao Shan in a dream, and told her that she should sacrifice her arms and eyes. She made arm soup out of it and had it brought to her father, who ate it and recovered his health. The rest of the soup was poured into the earth, and from it grew the Buddha’s hand tree. Even Miao Shan sprouted hundreds of new arms and eyes, with which she can help all of the suffering creatures in all worlds. Because there are many worlds and she cannot always be here, she has given our world the peacock, with its eyes that are meant to watch over us. She is an incarnation of the bodhisattva Guan Yin (the listener of the complaints of suffering beings)[1].

My painting, which was made before I knew the story of Miao Shan, shows a young woman in traditional costume.[2] She is holding the Buddha’s hand sculpture in her outstretched arm, like a giant fish.

[1] Guan Yin: 观音 . This bodhisattva of compassion is actually from India and is called Avalokitesvara there. He can take many forms, be embodied as a male or female. Merging within the figure of Guan Yin are both Buddhist and more ancient ideas, as was also the case with European saints. More than anything, Guan Yin fused Xīwángmǔ (西王母), the Queen Mother of the West (Taoism).

[2] The traditional costume is Romanian, not Chinese. Miao Shan is represented by the Romanian artist Marieta Chirulescu.

Text:

Xu Shuxian, Die Antworten (2011)

Xu Shuxian: The Answers (2011)

Exhibition:

The World of Gimel, Kunsthaus Graz 2011

The Guardian of All Things that are the Case, neugerriemschneider 2011

Catalogue:

Adam Budak, Peter Pakesch (Ed.), Antje Majewski, The World of Gimel. How to make objects talk. Kunsthaus Graz / Sternberg Press, 2011