Goods, 1999–2004

Flughafen Sofia 1+2, Goods 1

People are carrying goods around for various purposes, but the spectator of my paintings doesn’t really know what is in these boxes, bags, backpacks and so on. Some of the goods are objects, while others are information. Some get stolen, some have been bought, some are a gift, some have been lost or destroyed.

When I decided to start a series about goods, I had already done two paintings based on photos of the airport in Sofia, Bulgaria, where I once had to spend half a day on my way from Sri Lanka to Berlin.

A Chinese friend who started to do business in Sofia in the early Nineties said that the main advantage of Bulgaria was its lack of infrastructure after Soviet rule, which meant that any inexpensive good was welcome, and it was in the middle between East and West.

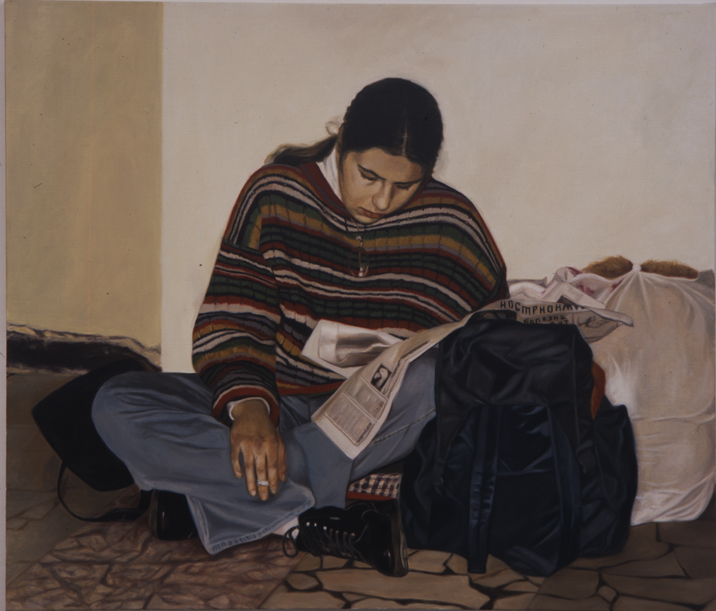

I painted one girl with an “Eastern” look, with her hand knit pullover, the big plastic bags and her cheap imitation slacker shoes. She is reading a journal with Cyrillic writing.

Then I also painted a young boy that looked very ”Western”, in his sportswear and casual bags, holding a soft drink, and finally a driver who transports the goods from the planes to the airport building for storage (Goods 1). I erased the labels on the bottles and blurred the slightly Chinese looking label on the box; they are just goods.

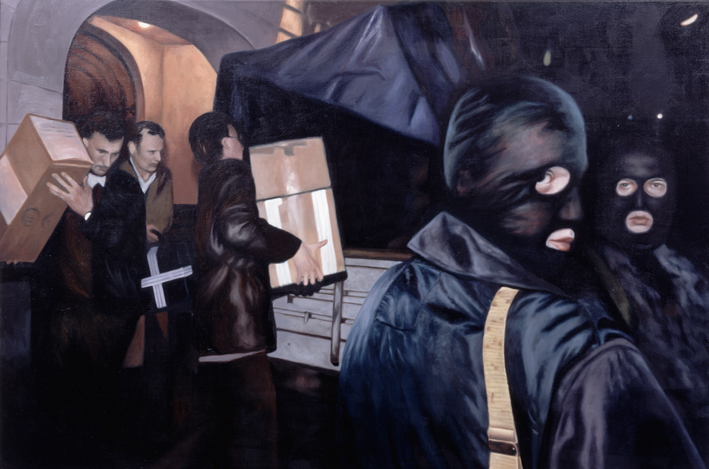

Goods 2

is a painting of the raid of the Gusinsky office of his media-emporium Media-MOST in May 2001. The Special Forces watching over this mission look very strange in their caps – like a cross between bank robbers and S&M-lovers. Putin didn’t have the right to do this, nor to deliver Gusinsky into the infamous Butyrka prison (which I painted in Prisoners). When questioned by journalists, he denied any responsibility. Gusinsky, one of the ”Russian oligarchs“, a wild entrepreneur who had made it from taxi driver to billionaire, had been among the financial backers of Jelzin’s re-election. His support had earned him, among other things, a license to run the first privately owned television network (1996). Even before that, he had been critical of the war in Tchetchenia and returned to his liberal and critical standpoints. When Putin came into power, he tried to eliminate this independent voice by not giving Gusinsky the loans he so desperately needed after a disasterous satellite-building project and the Russian economic crash of 1998. Gusinsky was released from prison after three days, partly due to the outcry of Jewish organizations and journalists worldwide, and took refuge in Israel.

The goods that are carried around in this case are illegally obtained information, and even if the spectator doesn’t know who Gusinsky is, he must feel the uncanny atmosphere of something done secret with a lot of power behind it.

Flood in Venezuela

is a rather big painting; again I had seen the image in a magazine and bought the image from an agency. Here, people are trying to rescue whatever goods they can; the car in the middle, the ultimate good, is turned over. Although it might still be saved,one can imagine how most of the goods these people possessed are lost forever.

Gusinsky first made money by producing copper arm rings for 3 kopeks and reselling them for 5 roubles. He then went into ladies underwear, copies of famous artworks and real estate; within two years, from 1987 to 1989, he had made enough money to found a bank, the MOST-bank which handled the finances of the city of Moscow, where mayor Yuri Lushkow was a good friend. When the MOST-bank ran into trouble, Gusinsky had already moved on into media. He owned newspapers, magazines, radio- and TV-stations, cinemas and film production companies.