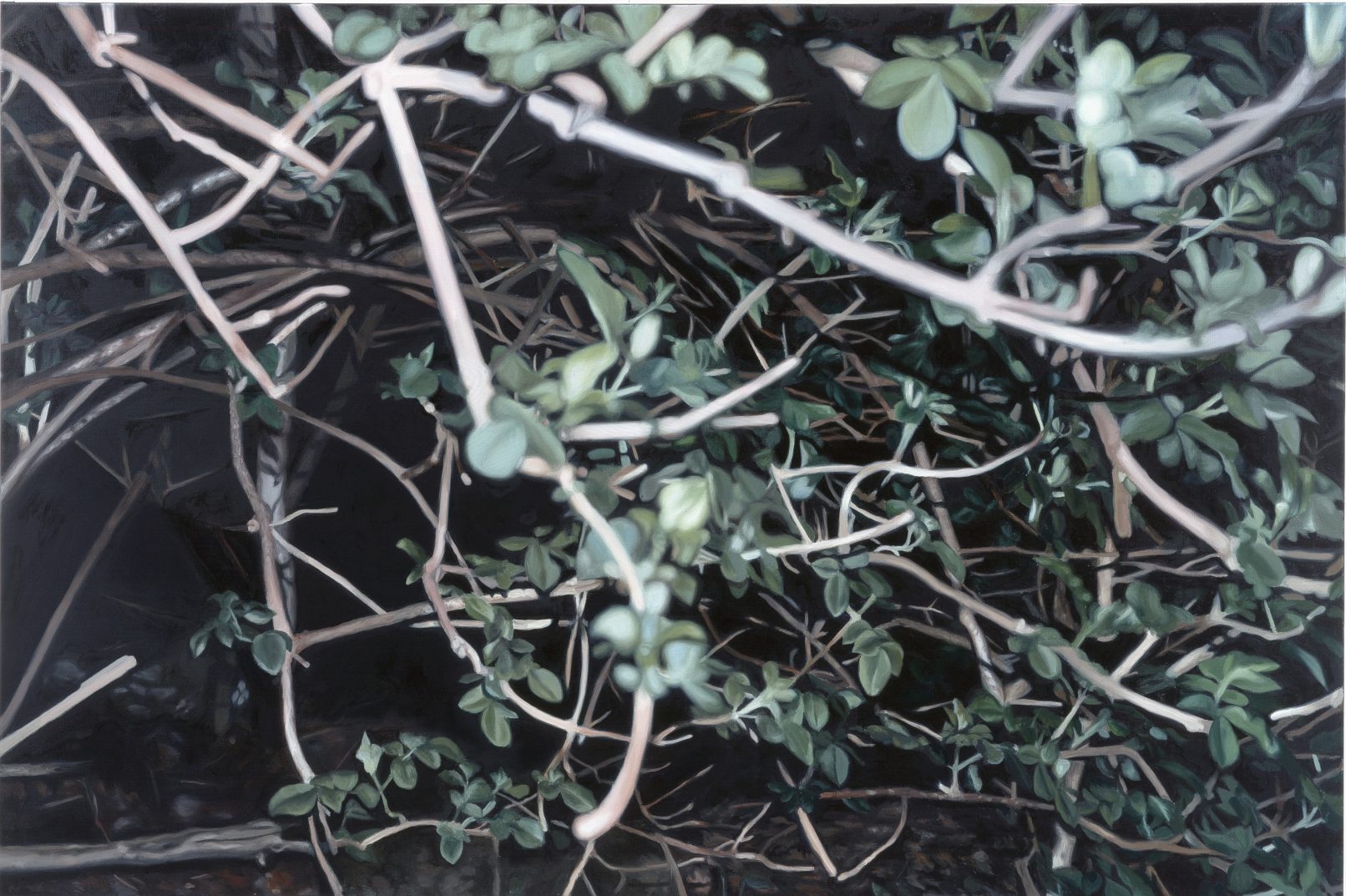

Einer zu viel, 2001

Die Streife entdeckt die selbstgebaute Hütte eines Landstreichers im Wald nahe der Autobahn (The Police discovers the self-built hut of a tramp in the forest near the motorway) (1998 – 1999)

The two series relate to each other in a number of ways. The first was based on a documentary that I had seen and photographed on TV at the same time: a documentary about the highway police. Nothing very exiting happened until they stopped next to a little foot path leading from the side of the road to the brush of a small forest caught in a triangle formed by three highways. The policemen followed this path and discovered some tiny vegetable patches and eventually a hut. An elderly man appeared; he was living in this shack like a hermit, all alone and far from the cities.

I later found out that the documentary filmmaker Gordan Godec had directed the film and phoned him. I was told that the police had had to take the tramp to the city; they found him a place in a house, where he seemed to be quite happy. In Germany, it is illegal to live on public property and use it to grow your own vegetables.

The policeman is actually taken from a film; I wanted someone quite young, curious. He might wonder why the elderly man would have choose a solitary life far from society. But the policeman’s role is to apply society’s rules. The tramp appears to want to be left alone, but he’s forced back into the company of others.

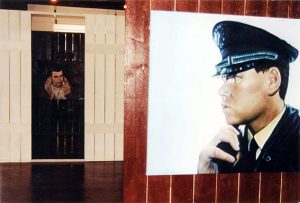

Die Gefangenen / Prisoners (2000)

The images for Prisoners were taken from a documentary film by Wolfgang Mertin (Die Hölle von Moskau) about the infamous Moscow prison Butyrka and the women’s prison at the Shtshjolkowskaja, that again I had seen and photographed from the television. The prisoners in these prisons had to share a bed with four others. They had no daylight, very bad food, hardly any medicine (with a lot of new cases of Tuberculosis), and near to no hope because most of them were expecting a life sentance. A new kind of social hierarchy was established inside the cells, with kings and pitiful underdogs. This society was even respected by the guards who warned the visitors, the first foreign camera team that was allowed into the cells (Mr. Mertin had been a correspondent in Moscow for the GDR television, speaks Russian and still has a lot of friends over there).

When I did the portraits of some of the prisoners that were interviewed, I found myself in the long and dubious history of depicting criminals. I was in the strange situation that I had taken the photos, but hardly remembered the interviews; to me they were faces a lot of things could be read into. When I finally saw the film again, I realized that I had misread these fixed images. I had interpreted them; once the people were in motion again, speaking, the softer ones appeared hard and the harsh-looking woman was actually a lost child.

These paintings are about the way we judge each other based on very little knowledge, and how these judgments can crush lives. I had been in St. Petersburg before[1], where we visited a friend who had just come out of several months in prison for the possession of one ecstasy pill. He was gay, which meant that inside prison he was praying every day that his cellmates wouldn’t find out about it. When he returned, he had developed a taste for esoteric religions and his feet didn’t fit into his shoes anymore; they were swollen so much from lack of movement. Prison in Russia means that society punishes you by sending you into a micro-society of criminals that judge you much harder than the judge himself – and you have to live in one tiny room with them for years.

The two series of paintings were shown together in Ulmer Kunstverein in 2000. A local workshop of handicapped people built two small huts out of raw wood into the historic setting of the Ulmer Kunstverein with it’s century old beams; one was painted a dark red, the color of clotted blood; the other a very dark green. Both huts were windowless and had small doors that faced each other. Standing in one of the huts, you were able to see some parts of the paintings hanging in the other; some cut-off faces with large eyes that staring back at you.

[1] The painting Der Schlafende shows my boyfriend, sleeping on the couch in our friends apartment in St. Petersburg. It was winter and very cold. The kitchen was full of tiny cockroaches that came in through the pipes, and I had a severe bronchitis.

View of the installation in Kunstverein Ulm, 2000

Thank you:

Wolfgang Mertin, Gordan Godec, the prisoners, the tramp, Friederike Kitschen.