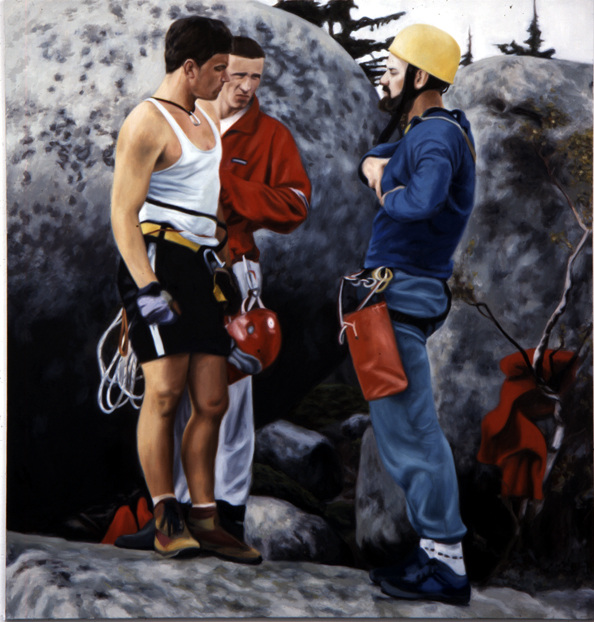

Die Bergsteiger, 1998

One of our journeys to Poland led us to the region of Klodzko County and on to the Gory Stolowe National Park in the Stolowe Mountains, which are part of the Middle Sudety Mountains. These mountains have been a tourist destination since the 19th Century, mainly because of their strange sandstone rocks. [1]

While we were walking through the sandstone formations, I observed and photographed a group of mountain climbers who were exercising on a rock wall. They were too far away for me to understand their words. Some of them were rolling up their gear, others debating over climbing methods. We wandered on, eventually taking a rest in a romantic mountain hut with a great view of the Czech part of the Sudety Mountains, when suddenly I discovered that all the inscriptions in the walls of the hut were in old-fashioned German, and here and there some visitor had carved a swastika next to them.

I was shocked, but not as shocked as when we encountered a Neo Nazi manifestation on the streets of Wroclaw, formerly Breslau. Three of my grandparents were born in what is now Poland, into German speaking families, even though my surname is Polish; but they all left for Berlin or Weimar before WWII and I was never very interested in the German stories of “Vertreibung” (expulsion), which were for me nothing much more than a nationalistic tale aimed at retaliation.

But history is more complex than that. The Klodzko Valley had been conquered and governed by Bohemia, Poland, the Habsburg Austria, Prussia, Nazi Germany and finally Poland again; and the Germans, mostly simple farmers, that were driven out of the area by Poland after WWII were replaced by people who’s story resembled their own: Poles from the areas that were given to the SU, from Ukraine and Byelorussia. [2]

In the communist era after WWII, there was yet another group of people moving voluntarily to the region: Polish intellectuals and artists who felt alienated and unwilling to compromise, and who were looking for a quiet refuge in the countryside.

At home in Berlin, I looked at the photos I had taken of the mountain climbers, and decided to turn them into a very large painting installation consisting of three panels. The size and the thematic recall the “manly heroism” of both Nazi and Communist paintings, but my mountain climbers are very normal people, nice guys with soft beards whose nationality isn’t obvious. They could be Polish, German or Czech. Their mountain climbing in the peculiar soft rock formations of the Stolowe Mountains isn’t heroic at all; no new race or state is built, nothing more is at stake then a leisurely afternoon.

I tried find a way around the history of how “naturalistic” painting had been used by both National Socialist and Communist regimes, and I found that it can be done very well just in the way a deeply compromised scene like that of men struggling against the mountains is painted.

[1] The relief of the Stolowe Mountains has been shaped through the last 70 million years. After the sea withdrew at the beginning of the Tertiary period, the folding of alpine system mountains begun, creating many fractures in the Sudety area. Tectonic faults and depressions emerged, e.g. Jelenia Gora and Klodzko Basins. The youngest, Cretaceous deposits reacted to those changes in deep fractures, which played important role in the relief formation as they delineated the main valleys and ridges. Therefore, at the beginning of the Tertiary the land was slightly declining towards the southeast, with a surface built of cracked sandstone. A long process of destruction, lasting ever since, lead to a division of the slab into ridges and separated hills, whose examples are now Szczeliniec (919 m a.s.l.), Skalniak (915 m a.s.l.), Naroznik (851 m a.s.l.), and Mnich (522 m a.s.l.). The Stolowe Mountains present a plated structure, unique in Europe, and make tremendous impression with their fantastically shaped rocks. The best-known forms are “Kwoka” (The Hen), “Wielblad” (The Camel), “Glowa Wielkoluda” (The Giant’s Head). A system of corridors has formed within the joint sandstone zone creating rocky mazes, which are particularly impressive and famous on “Bledne Skaly”

(The Errant Rocks). www.pngs.pulsar.net.pl

[2]On the interesting oral history site www.mountainvoices.org/poland.asp testimonies both Polish and German describe what it was like, and their memories are not all hostile towards each other. One old lady recalls that they came into an area “where the Germans were still living, they would come and bring things. They were good people … We lived in peace [with them]. The most difficult thing was how to communicate with them, cause they didn’t speak Polish and we didn’t speak German – we used gestures, but we were good neighbours … We were sorry for them…. We cried as much as they did [when they were deported], cause, you know, my parents, the Russians chased them away from their home as well, so we knew what it meant.”

Anonymous, F / 67, housewife, Poland 5