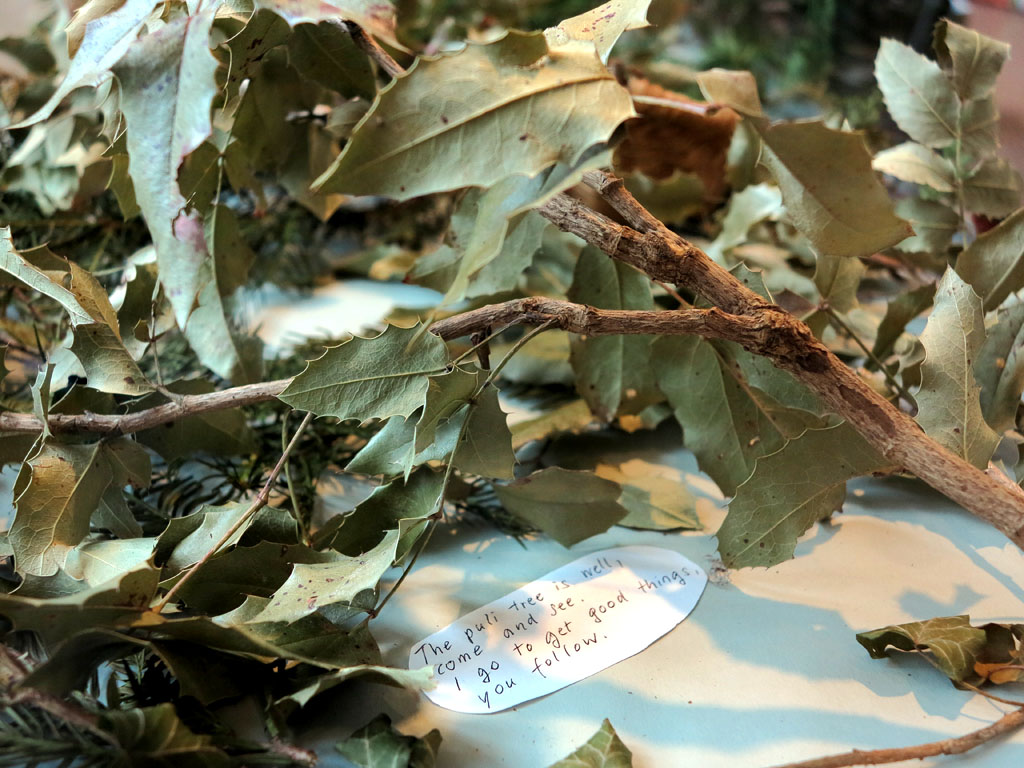

I go get the good things, you follow me, 2011

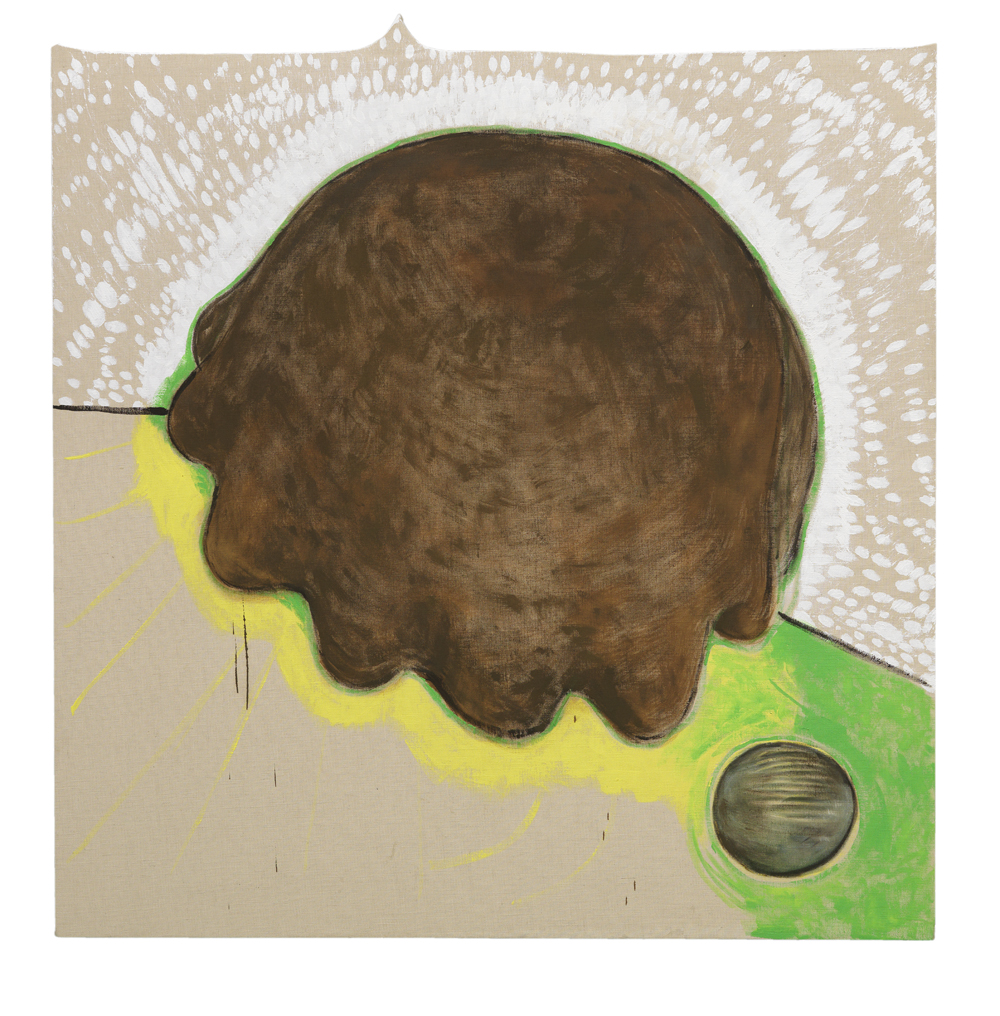

Since 2009, Majewski has been associatively following eight objects that are part of the Gimel World, her imaginary museum. One of these objects is The White Stone; both the stone and the basket that holds it come from her grandmother.

In the highlands of Papua New Guinea, kepele was the fertility ritual performed in times of crisis.[1] Everyone, even the hostile tribes, came together, ate, celebrated, and built a cult house together. “I give, you give, we all have to give.”

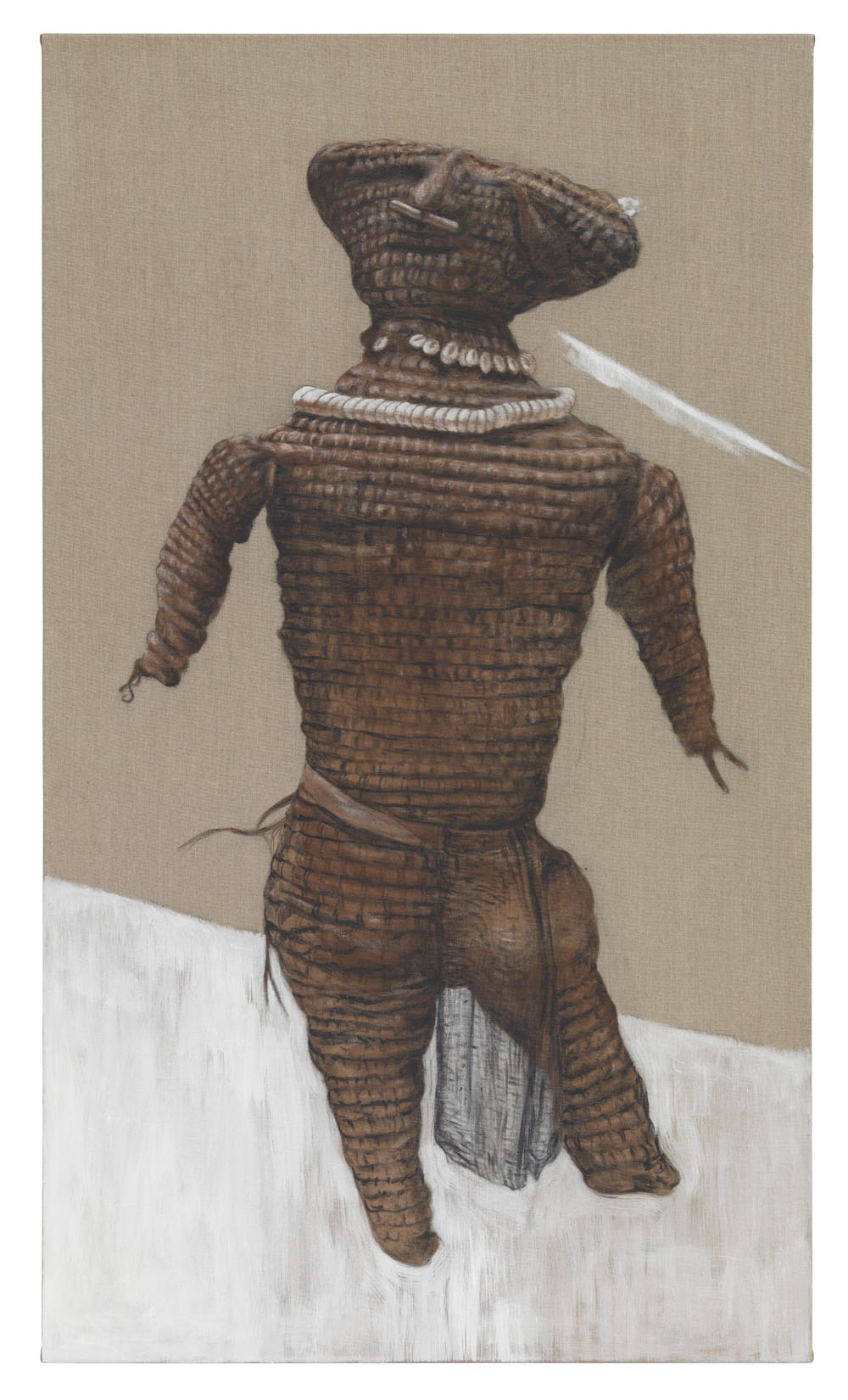

The yupini straw man was made to dance and placed next to the koulini stone[2] at night, so that they could have intercourse. While the straw man could stand for a mythical forebearer who came out of the forest at the time of the hunters and gatherers and can transform himself into a python rainbow serpent, the magical stone artifacts have only been venerated since the arrival of sweet potatoes some 350 years ago and embody a female ancestor who brings fertility. They were found while gardening and originally come from a much older culture about which nothing is known.

By sleeping together, the female stone and straw man brought the world back in balance, restoring fertility to humans, animals and plants. “Everything grows well. (…) I’m going to go get these good things, you follow me.”

Antje Majewski’s paintings of the stones are for example entitled Blaue Panazee (“Blue Panacea”). The titles come from the novel Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky,[3] about a zone in which artifacts left by aliens are found and discovered to obey a different set of natural laws. Without knowing exactly why they work, people use them to start cars or to heal people – much like the stones used for magical purposes in Papua New Guinea. A stalker goes into the zone to find a golden sphere that fulfills all desires. Upon finding it, he surprisingly wishes not for his child to be healed, but: “Happiness, free, for everyone and let no one be forgotten!”

The kepele ritual served the entire world, where there was no longer any distinction between the living and the dead. A man could become a serpent or a stone. When the ritual experts died, they became yupinis – they were weaved into a basket and buried standing.

We also need a ritual that brings happiness to everyone and reconciles the enemy tribes – in the knowledge that stones, animals and plants are our ancestors, our brothers and sisters.