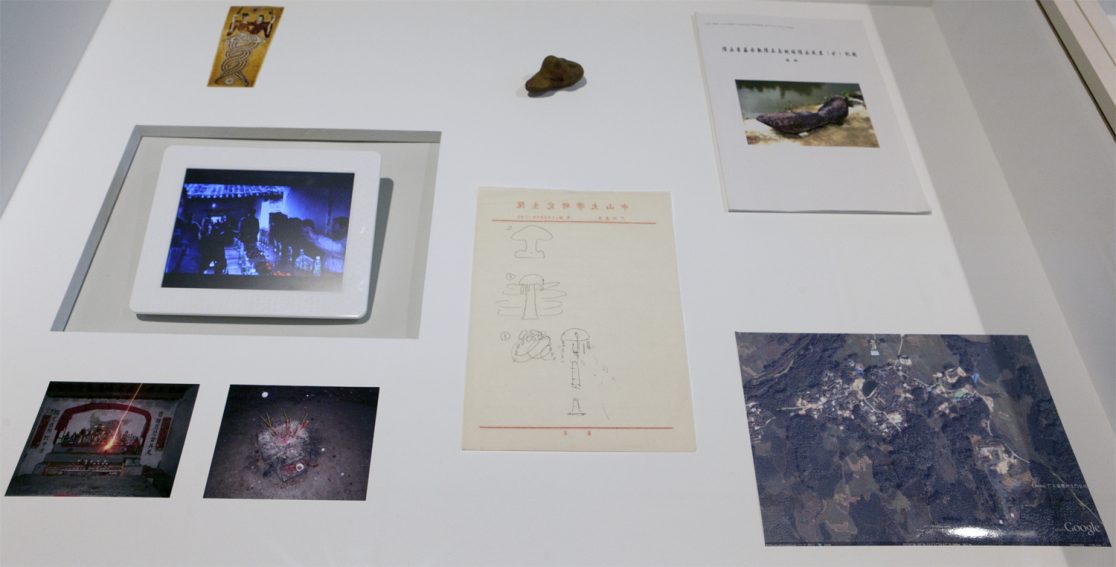

The Meteorite. Conversation between Lu Ling, the Villagers of Yang Wu Sha and Antje Majewski. Yang Wu Xia, 2011

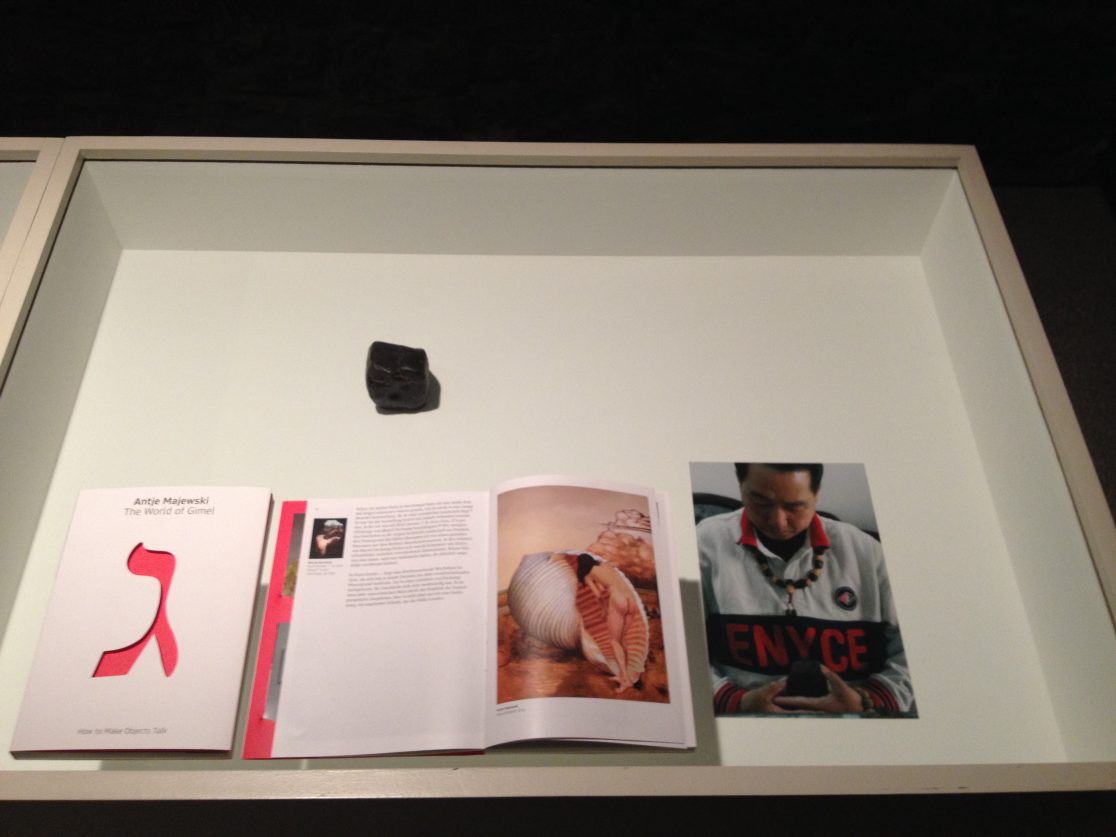

When I began the preparation for the exhibition World of Gimel in the Kunsthaus Graz from 2009 onwards, I occupied myself with seven items that I had collected during my travels. One of them was the meteorite. In order to better understand this meteorite, to pursue the “history of the country from which the object has come to you, the story of the men of this country, the women of this country” as Issa Samb had requested, I decided to go back to China in 2011.

I had originally bought it in Beijing, where I had spent four months in 2005. Going out onto the ring road for the first time, I was overwhelmed by the functional ugliness of the residential units, commercial units and mobility units regulating the masses of people. Everything was in a bright, tiresome grey, shrouded by smog and dust from the Gobi desert. It was only after a few weeks that I began to understand that there were angles everywhere, within which Beijingers lead a different kind of life: a wild growth that washed around the precisely planned, clearly outlined forms.

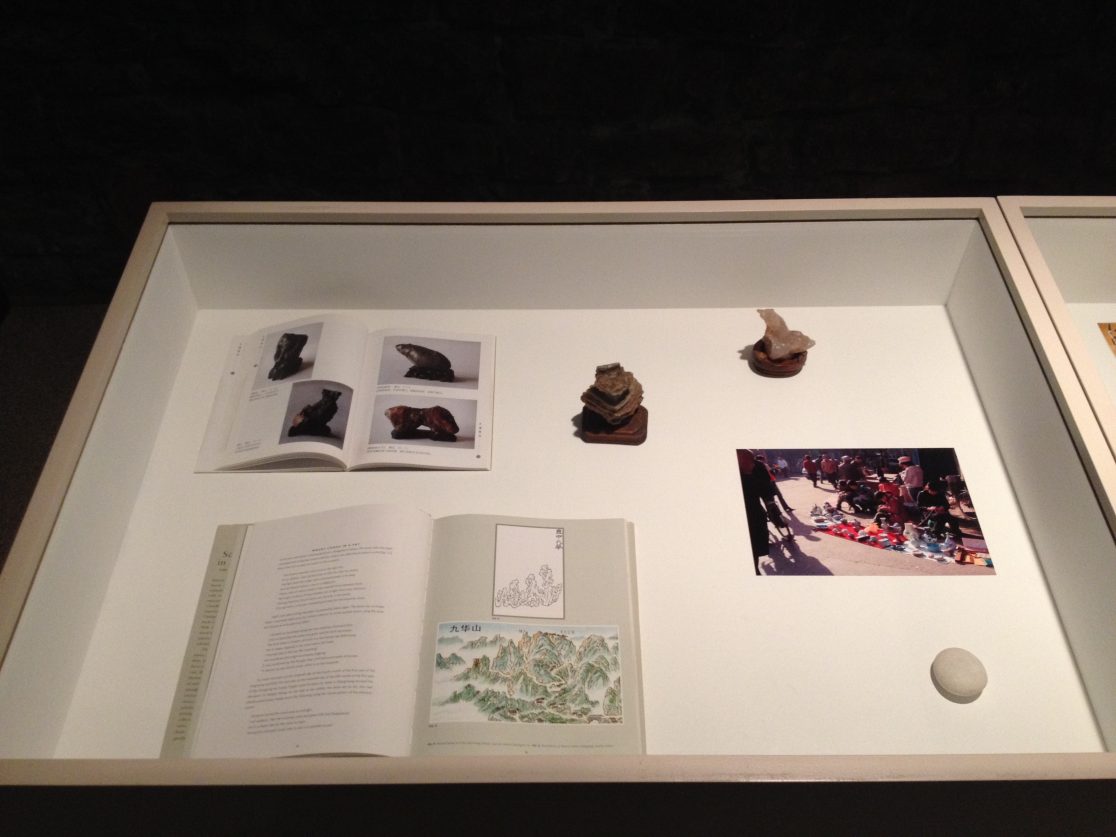

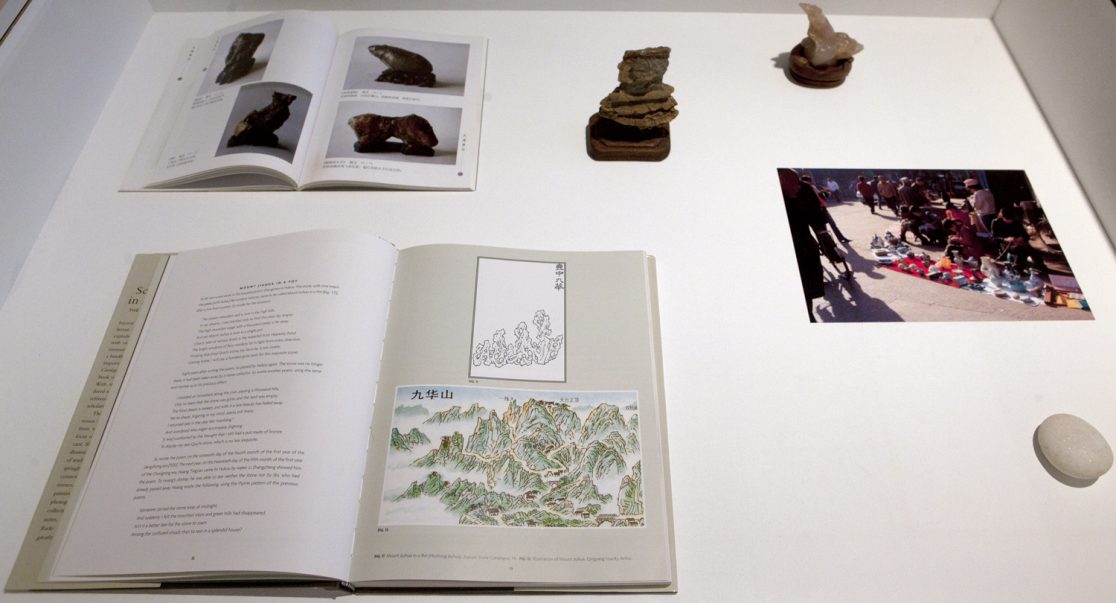

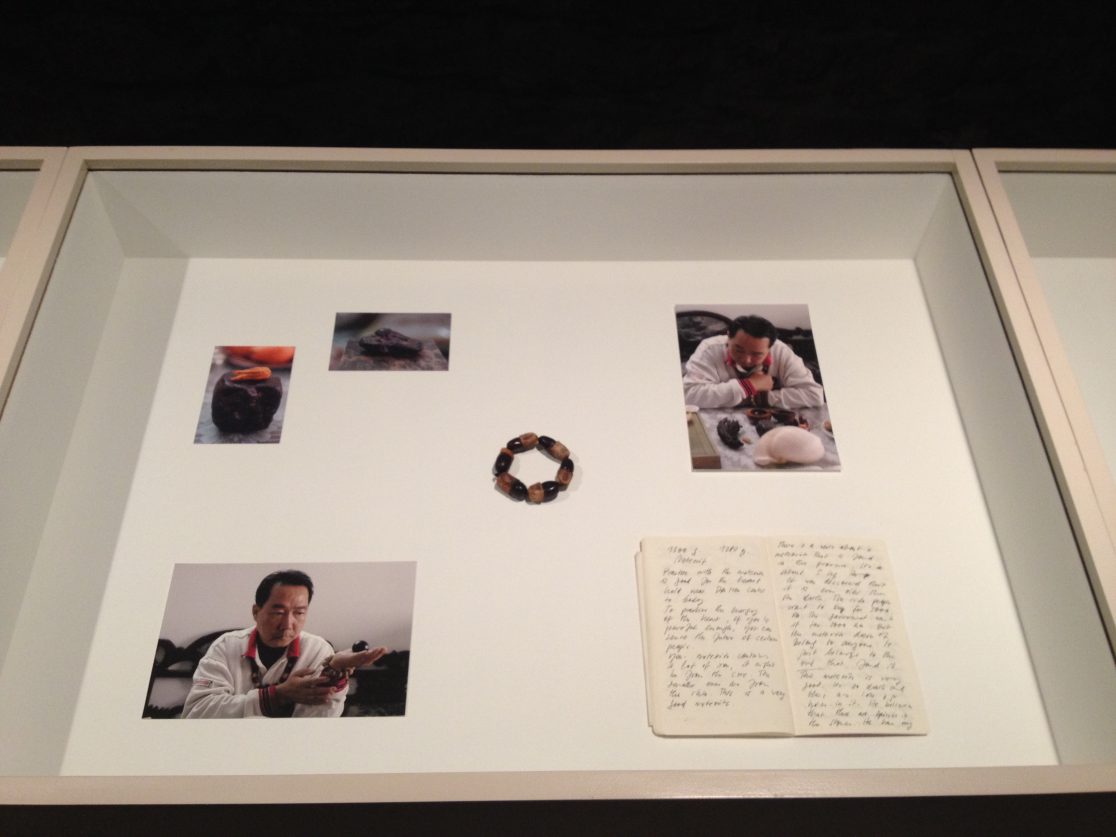

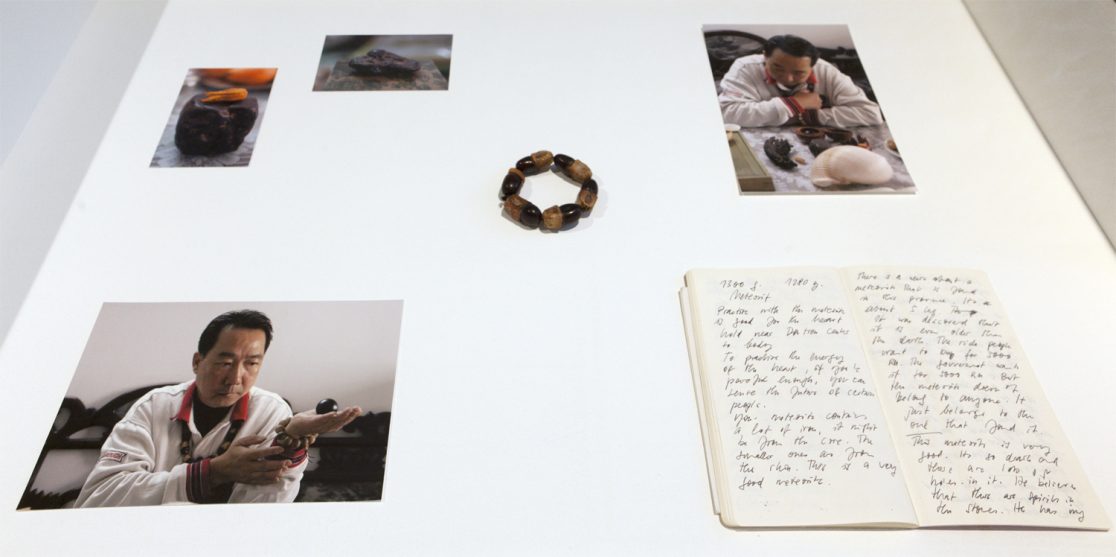

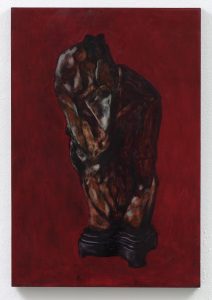

We met an American lawyer who knew the old Beijing like a ghost town under the new version; could say, for example, where there had once been a temple, in which street the clothiers had been. He led us to one of the few temple grounds that had an antique- and flea market, not for tourists, but for Chinese. And in almost every booth were things that seemed baffling to me but apparently were very valuable to the Chinese. I bought a meteorite, a teapot in the shape of a human hand and a strange, small, blackish sculpture that for a long time I took for a type of algae or jellyfish–in any case a sea creature. In addition to these, I also found three small, irregularly shaped stones that were to be placed on little carved pedestals. The meteorite is a heavy, magnetic boulder. I brought it home and placed it on an unstable wooden pedestal that originally used to be an African child’s toy. Thus it became a Gong Shi – a viewing stone like those which the scholars in China have collected and used since the Han-Dynasty (206 b.C.-220 a.D.) for the purpose of contemplation.[1]

I had bought several other small Gong Shi in this flea market. I tried to paint them, but wasn’t quite satisfied with the paintings.

Antje Majewski, Rare Desert Stone, 2005

See: No School Today

When I painted their surface, could did I depict? The essence which made them so interesting was, according to Chinese understanding, the capability to contain or circulate Qi – energy of life, breath. How could I depict the innermost essence of these stones? Unknowingly, I was contemplating one of the central questions of Chinese aesthetics, which concerns our relation to objects.

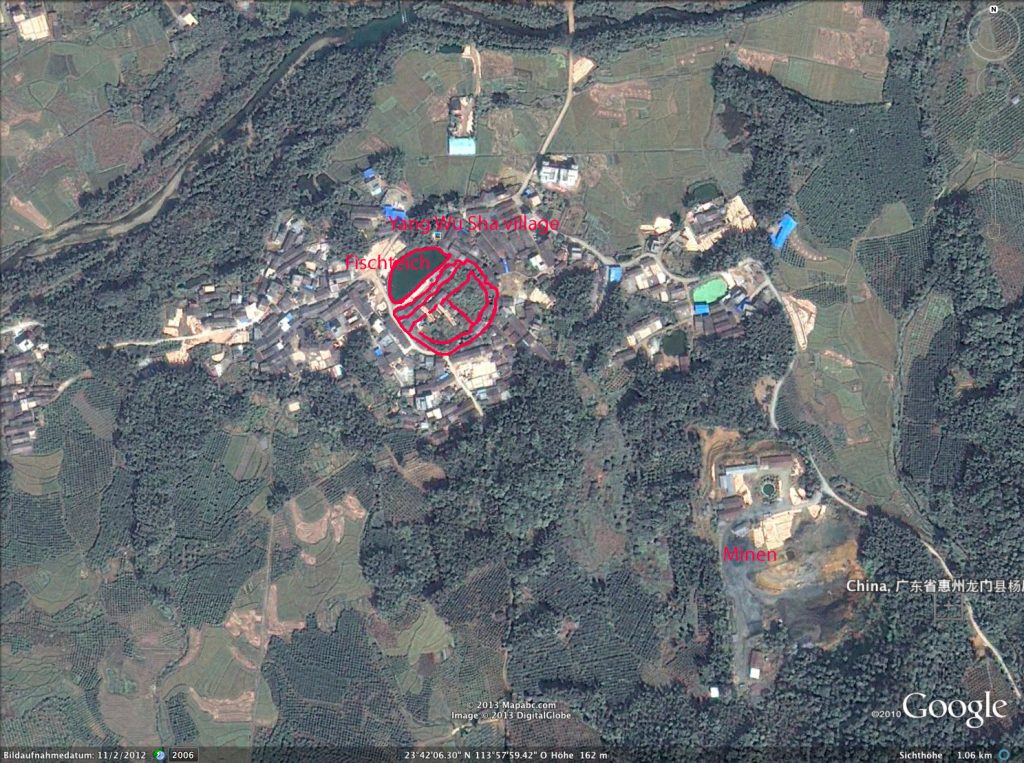

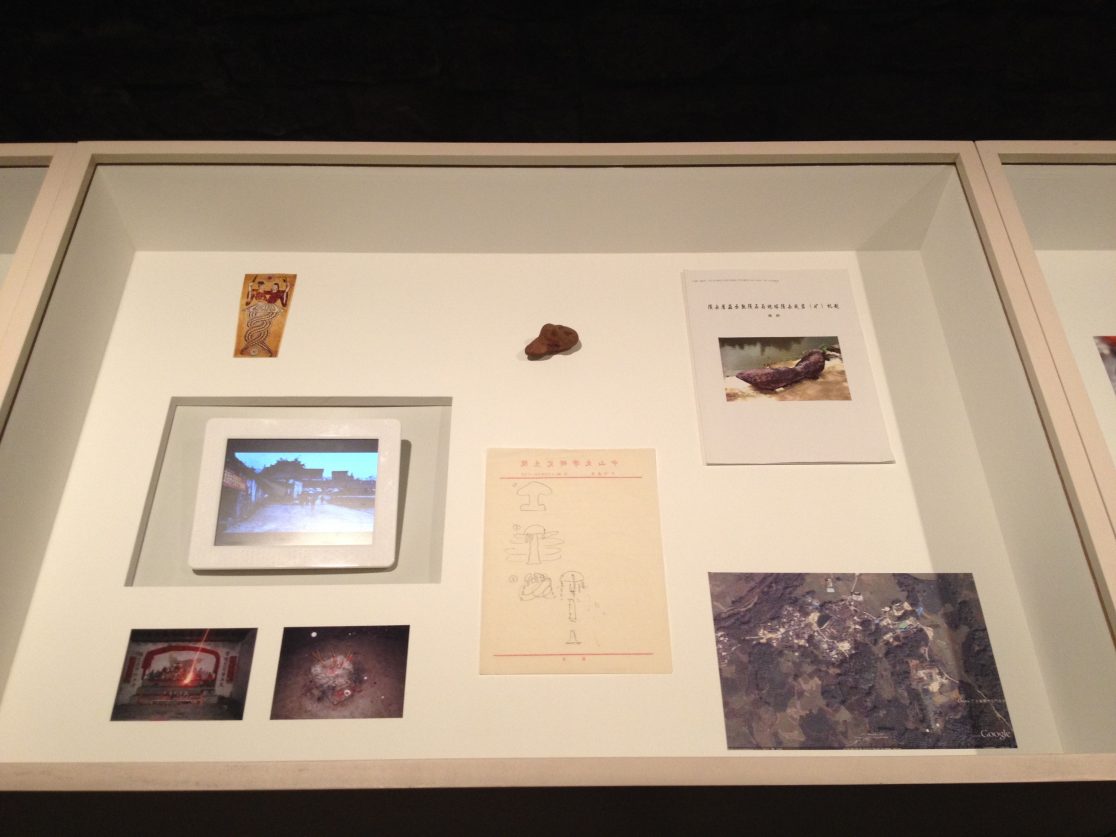

Though I had bought it in Beijing, it could have come from anywhere; and so I decided on the south of China where there are frequent occureneces of meteorites. In Guangzhou, I met the meteorite researcher Lu Ling, who studies meteorites as a “folk scientist.” Lu Ling explained to me her theory that all life on Earth was created from the shapes of clouds swirled by meteorites striking the primordial landscape. She wanted to take me to a village where they had found many meteorites, and had kept one especially large one, the Iron Ox, in front of an ancestral temple. Together with my research assistant and friend Xu Shuxian, who translated all conversations, we travelled into the most beautiful scenery of the Long Tan mountain In the village of Yang Wu Sha 杨屋厦 we were greeted by the mayor, and after many photos were taken, we were invited to a sumptuous meal.

I explained that I wanted to find out more about their meteorite. The villagers told me the story of the Iron Ox in several variations: a female ancestor wanted to fetch water and was frightened by a being that jumped out of the lake and said it was there to protect her and the village. Alternatively: the ancestors dug the pond 300 years ago and found the stone within. It was a monster and it ate all the fish. Therefore a Feng Shui-master had to strike a notch into its back with an axe. Then it was placed next to the lake, and is now seen as the protector of the village who brings luck to all. The children use it to play and ride on it.

We had to walk up into the mountains into one of the most beautiful landscapes I have ever seen. We walked over mountain ridges, through bamboo groves and came to a valley full of orange trees with fruit hanging everywhere. A stream flowed between large, round lumps of rock. Finally we reached the little cottage that belonged to the former village chief, which was behind two enormous, round boulders. He called them Yin and Yang. From them, you could see down into the valley and over to another, smaller boulder: Guan Yin. Standing on Yin, the old man told us another very interesting variation on this story. Here the “Iron Ox’ – also called “the beast” — had to be castrated by the Feng Shui master in order to finally pacify him. The small cut-off penis is said to have disappeared, maybe sold to a dealer of scrap metals. This story makes the meteorite into a tamed god of fertility, which can be useful in a rural area.

The old man also explained to me that a crack in the rock was used to venerate the god of heaven, Tian. Tian is also the order of the whole cosmos. On the way back, we passed a temple to the god of the earth. To me, it seemed very appropriate for a village like that one: standing in the centre is an ancestral temple, which reinforces the community and where weddings take place; in a field, a modest little temple to the earth god, to whom one brings some of his own fruit.

The modern world has penetrated even this remote rural village and brings along bad luck. The oldest layer of the narration on the meteorite brings in the sky goddess Nuwa, one of the gods of ancient China who lives in this village. An old man said that since the time when Nuwa fixed the sky with stones, they fell down and brought catastrophes: in this case, it was in the form of mines for rare earth minerals that are not far from the village; they poison the water and cause cracks in the houses. The villagers are caught in a conflict with the government, in which Lu Ling tries to mediate. The mine contaminates their water and pollutes their agriculture. The entire village, a 300-year-old complex built according to the principles of feng shui, should be resettled. In today’s China–where rapid industrialization is conducted at the expense of the environment–there are countless local-level conflicts like these, which can quickly become life-threatening for the villagers.

My interest in the Iron Ox was used by the villagers as an argument against the government’s plans to relocate the villagers. Instead the water should be treated and the area should be opened to tourists like myself. Because of this, I was not only entertained, but also very often photographed with various groups. The photos of me were hung in the ancestral temple, along with a nice thank-you note that I composed with Shuxian’s help, and the ecologically minded mayor was elected to head several villages shortly thereafter. May the meteorite that brought me there bring them luck!

Another journey to Guangzhou brought me back to the village in 2014, together with my students. The villagers have not yet been relocated, and the village with the Iron Ox now appears in a tourism guide. Just now they plan to create a museum for the Iron Ox, in which they want to show my video as well.