AM: Rajeev Balasubramanyam has just spent a year in Berlin, writing his second novel. It’s his last day before going back to a little cottage near the English Sea, to have some holiday and see his girlfriend. I shudder at the thought; it’s very grey and cold outside. Rajeev hasn’t decided yet if he wants to come back to Berlin to finish his book.

Arnold Böcklin, Die Toteninsel, 1883

RB: I like that one!

AM: It’s by Arnold Böcklin. The Island of the Death, his most famous painting. It’s funny that you walk straight to it.

RB: There’s nothing else interesting here.

AM: And what interests you in this one?

RB: Well, it looks like it’s come from a dream. And this stuff cut of a rock in the middle of a big piece of water. What I thought it was – was a kind of King Arthur thing when they take the dead guy off.

AM: I think it’s supposed to be Charon, who’s the ferryman in Greek mythology, and you have to pay a golden coin.

RB: But who’s the person in white?

AM: That’s a dead person.

RB: It reminds me of that film as well. This Orphee by Jean Cocteau.

AM: I have never seen it.

RB: Oh, it’s great. It’s really good. It’s about – death comes to life. Taking people back and forth. – It was the sea, that’s why I came here first. It was the water. It looks very still and consequently austere but I like it a lot.

AM: Is it rather gloomy?

RB: No, not for me. It’s very peaceful, that’s why I like it. And once I’m very tired it looks like the kind of place I’d like to go. Whether alive or dead I don’t really care.

Arnold Böcklin, Selbstbildnis mit fiedelndem Tod, 1872

Arnold Böcklin, Selbstbildnis mit fiedelndem Tod, 1872

AM: Böcklin apparently was quite obsessed with death. That’s his self-portrait.

RB: What, with this scull playing the violin?

AM: That’s death fiddling a tune.

RB: That is him, is it? So he’s always thinking about how he’s gonna die.

AM: But I think a lot of it was also theatrical.

Arnold Böcklin, Beweinung unter dem Kreuz, 1876

RB: That’s by him as well. „Weeping at the cross“.

AM: That’s really over the top. I quite like the Christ, though. Anatomically it’s not correct, but it’s so heavy. What do you think?

RB: It’s just this colour; I wonder why it’s done with that colour. It looks like the moon. And because I’ve been reading about how Christ is meant to represent the sun. The cross – there’s been a big debate about the phases of the sun and the zodiac and this kind of thing. And then some people paint him looking like the moon.

AM: Where did you read that?

RB: Oh, one of my books. (Both laugh.) I’ve many books about these things. It’s all about…Because Christmas is the birth of the sun from the 22nd, when the sun symbolically dies and then comes back on the 25th, that kind of thing. How all the Christian festivals are on top of pagan festivals. Very interesting.

AM: And why does it interest you?

RB: Oh, for many reasons…because I’ve been reading about how it seems that all religions come from Sumer, and a lot of it is Sun worship, and Islam is a kind of Luna religion. And it seemed to me that a lot of Hindu gods and Christian gods are actually the same people.

AM: Do you think so? Who for example?

RB: Indra in Hinduism would appear to be the same guy as Thor.

AM: But Thor is not Christian.

RB: No, I’m talking in the sense of northern Europe. And who would appear to be the same guy as King Arthur, I’ve been reading.

AM: It’s funny, I think in this painting you don’t really know if it’s supposed to be night or day, it’s kind of caught between.

RB: It looks like Jerusalem to me. I went to Jerusalem, it looks like Jerusalem.

AM: I don’t know much about the life of Arnold Böcklin, probably…

RB: …he might have been there. – Who is this lady with the very nice blouse? She is the only one that looks like the moon as well. And with red hair like him.

AM: I think she’s the sinner, Mary Magdalena. Do you know the story? That she sinned and people started throwing stones at her…

RB: Oh yes. And he said…

AM: And there is also a theory that she was Jesus’ companion.

RB: I’ve been reading a lot about this as well. And how for some people she’s the centre of the entire religion. Particularly in Languedoc, South France. They take her bones out every year and parade them. And for them, the religion is about her and not him.

AM: Not the other Maria?

RB: No. It’s just her. And they are saying that in those times she was actually kind of pretty much the centre of the whole religion but then she was suppressed and she went off to France to continue the religion after the political movement was overthrown with this fellow…and it also says, this other book I read, how he was responsible for killing John the Baptist.

AM: Who…Ah, Jesus. (Both laugh.)

AM: Over there, that’s Hans von Marées. He did all those experiments on his paints. You can virtually not see the paintings any more because they have become so dark and they crack so much. He used a totally wrong kind of oil in the paintings. But I don’t like him that much anyway. I really prefer Böcklin because at least he dares to be very kitsch, whereas Hans von Marées for me is more this masculine kind of symbolism.

RB: Let’s go, yes?

AM: We can stop wherever you feel attracted to. But I’d like to know what you think of this one.

Anselm Feuerbach, Miriam, 1862

Anselm Feuerbach, Miriam, 1862

RB: Not – very much.

AM: No, I was just wondering. This was the painter I loved first when I was a kid. We were walking through the museum in Wuppertal, and I wrote down what I liked best. I still have that piece of paper, and it says: Anselm Feuerbach, that’s the best! I was about eleven. I think what I really liked about it was this dark hair. And also the fact that his women are always quite strong, they are very upright and they have very strong necks.

RB: I don’t think I have to say anything about this. Looks around.

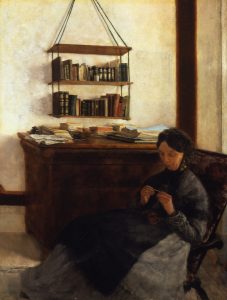

Wilhelm Trübner, Auf dem Kanapee, 1872

AM: This is a little painting that I quite like. I don’t know why.

RB: You like this?

AM: Yes.

RB: That’s an ugly woman. I don’t want to look at her.

Arnold Böcklin, Bildnis Angela Böcklins mit rotem Haarnetz, 1863

AM: This is the wife of Arnold Böcklin. She was Italian.

RB: The Hair is nice.

AM: He brought her back from Italy to Germany, I think. And I think she wasn’t very happy.

RB: I never really know what to make of portraits.

AM: What do you mean?

RB: Well, somebody I don’t know, and – somebody’s drawn them, and – fine, ok. But, apart from that – I don’t really get very much else out of them.

AM: So, the way you look at a painting – is it all about content?

RB: No. But to me it’s just not very interesting. This red stuff looks nice.

AM: But isn’t that something you can get out of it? I mean, if I look at this very strange headgear – for one, I’ve never seen something like that, I don’t know what material it is. It’s very fluffy and soft, apparently, and it has little pearls in it – and then the next thing for me would be to see how it’s painted. I like the way it’s roughly painted and you can feel the material.

RB: Me too, but it’s still – if you hadn’t stopped here I wouldn’t have stopped.

- AM. Ok, then let’s go on and stop at the next one you want to stop at.

Arnold Böcklin, Ruggiero und Angelica, 1873

RB: This is cool.

AM: So you really like Böcklin!

RB: Oh, is it him again? (both laugh.)

Yeah, I mean I like this serpent thing, very nice colours –

AM: – it’s very turquoise –

RB: – very frightening. And it’s a bit of a kind of a man’s wet dream, really. Cause it’s got violence and fear and some naked woman and then the guy with the long phallic thing walking towards it but, ah…I still like it. I like the snake.

AM: Don’t you think it looks a bit funny? (laughs.)

RB: Well, he’s kind of smiling, he looks a bit human.

AM: No, he looks a little bit like a dog who knows he’s going to be beaten, who’s done something wrong.

RB: Yeah? I think he looks a bit bored by the whole thing, really.

AM: And one really doesn’t know what this snake wants from poor Angelica.

RB: Who is Angelica?

AM: The woman in the middle. – I think it’s really funny. For me, Böcklin is mainly – it’s really humorous, most of his stuff, for me.

RB: You find this humorous?

AM: Yes, definitely.

RB: But I’m not sure if he meant it to be.

AM: I think so. He’s done also a lot of paintings with mermaids. They are playing in the waves, and they are very good-humoured. I mean they are quite fat women who play around and who laugh loudly. And there’s always a bit of tastelessness about his paintings. Even the Island of the Death is for me a little bit tasteless. I kind of like that. It dares to be tasteless and to be very populist and…

RB: That’s not why I like it, though. I like it because I relate to the images. It’s all very sort of surreal. I like the colours. I like reptiles. They are always in everything. In every single mythology, there’re always reptiles.

AM: Well, of course, because people were so afraid of them.

RB: I think it’s because they are afraid of what reptiles – well, part of the human brain is reptilian, right? And that’s the part that behaves in this ferocious way. It’s all based on fear.

AM: Actually, I have just seen a film, “The Relict”, do you know it?

RB: No.

AM: It’s a kind of quite Ok Horror Movie, but it’s not really great. In this film there’s a scientist who went to Brazil, and he sends back to the Natural History Museum he works for two boxes, and one of them seems to be empty. It only seems to contain some leaves. They analyse the leaves and find out they have actually some kind of fungus in them that is drained with hormones. And whenever any animal eats the fungus his whole – of course it’s very unscientific but his whole DNA gets mixed up with other DNAs and it turns into some kind of monster. And the scientist himself has turned into a huge reptile that also looks like a wolf. And he needs part of the Hypothalamuss of human brains where this kind of hormone is produced or something, so he has to cut off peoples heads in the museum. It’s a huge monster. And they analyse a bit of slime of this monster and they find out: “Oh, it’s thirty percent human!” and they can even find out who it is, it’s that scientist. Who was always a very bad colleague. (laughs.)

RB: It’s just crazy how again an again and again and again in just about every single historical record you hear of hybrid species being created between human beings and animals and reptiles and…it just continues and I wonder if it maybe happened at some point.

AM: What!

RB: This…Hybridity. (Both laugh.)

AM: In the film there’s an old scientist who believes in it. And he’s overwhelmed with joy when he finally looks into the eyes of the monster. Because that proves his theory, right. And then of course, the monster eats him.

Gustav Spangenberg, Der Zug des Todes, 1876

AM: So what do you think of this one? Did you stop deliberately?

RB: Yes.

AM: Can you describe the painting? Because we can’t print them.

RB: There’s this very feminine looking death monster thing, a skeleton walking in the front with a bell (Laughs). Three children, one of them is carrying a reed and they’ve got reeds on their heads – which is another symbol. More children behind. Someone wearing a very nice red cloak, carrying rosary beads. And a bishop. Old poor looking guy on crutches, actually not that old, but poor. Some important weasel on a horse.

Landowners. Rich people. Poor looking people.

AM: I think that’s meant to be a virgin, the one in the white veil.

RB: Yes. And it just goes on and on and on. And then this woman in black. Who seems to be asking death something.

AM: I think she’s asking death to take her with her. She’s tired of life; she wants to go with them.

RB: She’s suicidal.

AM: Yes. Whereas on the right hand side we have a beautiful young woman who says Goodbye to her soldier friend. And he goes to join the march of Death. – Do you think that’s a good painting?

RB: I like it, yes.

Lesser Ury, Nollendorfplatz bei Nacht, 1925

RB: Where is this?

AM: Nollendorfplatz. That’s in West Berlin. Does it look for you like the Berlin of today?

RB: It does.

AM: It’s by night, you can see lights. It’s quite roughly painted so you can’t really distinguish the cars from nowadays cars. It could be raining.

RB: Maybe, maybe not.

AM: But it does give you strongly this feeling of a big city by night, even though you don’t see anything except a few lights.

RB: It reminds me of looking out of the window in that place we were after I had cut my finger –

AM: Oh, in Karl Marx-Allee.

RB: It just looks very big and very powerful and not very human.

AM: Do you like cities to be really big?

RB: Not necessarily.

AM: Would you ever live somewhere else than London?

RB: I’ve never really lived in London, to be honest.

AM: Oh really?

RB: London is too big.

AM: Berlin is a size that you would prefer?

RB: Maybe. I’m not sure.

Curt Herrmann, Schloß Belvedere bei Weimar, 1912

RB: I like this, too.

AM: It’s pointillist. Very bright colours. If the other one was all about the night, this one has very bright daylight.

RB: I don’t know what to say. I like both of them.

AM: But if you say of a portrait, you don’t know why you’re looking at it, it’s just a person, I mean this is just a building. So why…

RB: That’s true. I have to think about this question.

RB: I have nothing to say, unless I make up some bullshit, so…(laughs.) Maybe it might be better to look at some paintings. I really enjoy looking at them. And then we talk about them.

AM: Ok.

RB: Because otherwise I’ll just keep on saying: I like it.

AM: Yes, whatever you prefer.

RB: Whenever I look at paintings I don’t feel like talking because I’m not using that kind of the brain. Unless it’s a painting with a lot of symbols in it, then you’ve got to use your – whatever kind of the brain it is.

Louis Eysen, Mutter des Künstlers, 1870

Louis Eysen, Mutter des Künstlers, 1870

AM: Oh, that’s a really nice one.

RB: It’s really skilful, right. It’s really real. But, ah…

AM: It’s so soft.

RB: Hmm. I think it’s because when these people – they are real people, they look realistic – I might not like them.

AM: As people. Well, this one probably not. It’s the mother of the artist. 1870. Yes, she might be really boring, that’s true. She has her own little small life, nothing is happening.

RB: If she’d met some twenty-first century Asian guy, she’d probably tell him to fuck off and have him executed or something, you know. That’s why I don’t really feel very sympathetic all the time. (laughs.) I think that’s probably why, I don’t know. I think if I was looking at portraits of Indians or Africans I’d feel quite different.

AM: You’d feel more sympathetic.

RB: Yes. I wouldn’t feel like getting hostility from these people. It’s more hostility…

AM: Just by her sitting there. She’s not even looking up.

RB: If I’d be in the room, she’d be looking up. (laughs.)

AM: I think if this elderly women really could have seen someone Asian or African at that time rather then being hostile she would have been astonished. It would have been so out of her world. Their world was so small.

RB: But that’s enough for me to feel instantly unsympathetic towards a person. I wonder if a white person goes to a gallery of Chinese portraits – but you don’t get Chinese portraits that realistic – but if you did, would he feel the same way that I feel looking at these portraits? Because if I look at this guy over here – or this guy – these are not people I would be talking to. Like under any circumstances, ever.

AM: (laughs.) I wouldn’t either.

RB: No, but maybe your great-grandfather looked like that when he was younger.

AM: Yes, you’re right.

RB: I hope your great-grandmother didn’t look like that. (both laugh.) But with landscapes or buildings that’s different because the social individual – you know, the personality is taken out of it and the human individual is taken out of it. It’s buildings, cities – expressions of individuals. And with a lot of white writers, I can enjoy reading their work but I don’t like the people. Or if I met them, I wouldn’t be very interested and I wouldn’t want to hang out with them, but I can really enjoy their work and I found that several times. I only respect them as far as them being writers, not as people, right. And I think that might be the same thing with cities or landscapes. I mean, landscapes, you can really detach from people, I would say. You can live in a city and really like the city while disliking the society and the people, that’s perfectly…unless the city is really in your face like London. It’s just sort of statues of mass murderers everywhere. If they’d tone that done a bit…(both laugh) you can’t dissociate yourself from the political implications of the architecture. But you can still really like the city, even if the people you associate with the city you don’t really feel you have much in common with. And with landscapes, you’re going even further; it’s just a landscape. And a human reaction to a landscape is not a very…

AM: But do you think it’s very general? Would it be the same with every portrait in here? Or does it depend on the person that is depicted? Would you read something into their minds?

RB: I don’t know, we can go and have a look at some more of them –

AM: But so far you haven’t seen anyone you found sympathetic?

RB: Well, these are all things I would really just walk pretty much straight past. This one, it’s a skilful work. But when I saw it – you didn’t see it, but I went “pffh” and you went “wow”! I have just no interest in this woman. – Yes, maybe she’s a nice person.

AM: No, I don’t really think so. Actually I didn’t say it because of the person. It’s funny how our whole education of course goes towards taking a painting more or less as a kind of abstract surface. Even with me, I still look at them very much like that. Probably it’s also the fact that I’m myself a painter so I always try to steal away some kind of technique.

RB: I have no form of education when it comes to painting. So I just look at them.

AM: What I mean is that we are taught to look at them without really looking at the subject; whereas I always think the subject is so important. But even for me…but I think there comes in this other thing that I like certain techniques and want to know how they did it. The colours or the way it’s so softly painted, I’d like to do something like that. Not like this one, this is too shy for me; the whole painting is so closed in.

RB: Well, I told you, if it hadn’t been for you I would have walked straight through this room.

AM: Let’s go on, then.

Arnold Böcklin, Selbstbildnis mit dem Weinglas, 1885

RB: We’ve done this…Yes, like this guy! Some fat, port-swigging git! Who is this?!

AM: This is actually a self-portrait of the painter you liked so much, Böcklin – (Both laugh loud.)

RB: Shit, that’s the proof of what I’ve been saying! You can like some of his work but not like them! I was saying it’s this fat, port-swigging old git and it’s actually…

AM: I’m very very sure I wouldn’t have liked this man.

RB: Well, you don’t know.

AM: Oh oh oh, I know.

RB: I suppose if we look at him again. See, now I’m trying to look at these people and feel nice towards them.

AM: No, you don’t have to!! (laughs)

RB: But I’m trying to, out of general human goodness. And then I think, he’s kind of cuddly, and you know, people with moustaches or something…

AM: But for me, if I look at him all I can see is like a very sure of himself old…

RB: He just exerts his power, isn’t he?

AM: Yes, power. He wouldn’t have talked to me in terms of me being a colleague or so, you know?

RB: Maybe, it’s just…he has weird hands. His hands are gone.

AM: That looks more like a gauntlet.

RB: It looks dead.

AM: True.

RB: Well, I don’t know. Now that I’m looking at him again, now I know that he is the artist, it does make a difference. Because before, when I’ve seen an old oil painting like that, I’d think it’s some rich fucker who hired the painter to do it, and he had to do it because of the money, and he did it so he could show off how important and wealthy he is and put it on peoples walls and then I’d just think: Fuck off! You don’t even deserve to be in a Gallery!

AM: And you think, if he’s the painter, he’s allowed to present himself in that way?

RB: Well, then you’re feeling he’s not doing it for such reasons.

AM: Probably yes. He can hang it in his studio and he can show people: “Look, that’s what I can do to a person. You see me here standing in front of you, do I really look that grand?” And then people want him to do their portraits.

RB: But now that I’m looking at him again I’m thinking, maybe he’s actually a quite unhappy dude. He’s not very happy indeed.

AM: There’s something in his eyes that is really quite melancholic. Even depressive.

RB: So now I’m feeling more sympathetic.

AM: Aha.

RB: We’ll see what happens when we look at more portraits.

In:

Neue Review No. 4, Dec. 2003, p. 34 – 37