Imagine a female artist, in the late fifties or early sixties in New York, decided to become a painter. She would have known but very few other female painters, in spite of seeing little else than painting around her. In college she would have tried to paint like her role models, but it wouldn’t have been a role written for her sex. Going out it was the tiring role of the groupie that was designed for her. The Club wasn’t open to women who could compete with the new heroes of the free world.[1] What would she have done in the years to come? What would her options have looked like?

Would she give up painting? Why not. Every other form of art looked fresher.

The second possibility would have been to have confidence in the universality of the (gender independent) language of art and in her work’s inherent “quality”, which, in the case of Agnes Martin or Bridget Riley, was reasonable enough.

The third possibility was to believe in an essentially female language that differed from the dominating male one. Judy Chicago, Miriam Shapiro and Lucy Lippard tried to spot a tendency for centricity in the abstract paintings of female artists: the “centre-hole thesis” was born. When this truth that had been shadowed by the formalism of the men’s art world was unveiled, it led quite naturally to “cunt paintings” (or “centre core imagery”). The predilection of female artists for soft organic forms and holes in the centre was easily associated with the female body, especially the womb or the vagina.[2] Springboards for the men, lifesavers for the women.[3]

The Pattern and Decoration Movement could be seen as a peculiar combination of possibilities two and three: grown on feminist ideas, in its presentation compatible with what was seen as art, in its content compatible with the idea of the new self-conscious woman. An astonishingly high number of male artists claimed their joyfully Matisse paintings and interieur to be inspired not so much by the quilts and needlework of The American Mothers but by The Orient, that imaginary female half of the world.

Finally it did make a great difference for the female artist whether she happened to be Afro-American, Chicana, Asian American or Caucasian. In the first cases, the chances of her having gone to art college were low. She would have often felt left out not only by her (white) male colleges but also by the Caucasian feminists in the 70s who outnumbered them in associations such as the “Women artists in Revolution (WAR)”, in conferences and the first feminist group exhibitions, though there were stars like Faith Ringold or Betye Saar.[4]

Afro-American artists have been forming protest groups since 1970 to organize actions and exhibitions. The fact that at the same time there were feminist group exhibitions that showed exclusively white (like SoHo20) respectively black (the group “Where we at”, Nyumba Ya Sanaa Gallery) female artists shows clearly that the division along ethnical lines worked just as well inside the feminist movement.

Chicanas and Latinas were in most cases less interested in taking part in any gallery scene. Around and after 1970, groups like the “Mujeres Muralistas” or temporary neighborhood collaborations headed by artists like Judith F. Baca, Tomie Arai, or Juana Alicia, tried to connect to the tradition of populist Mexican murals. Their work wasn’t aimed at an art public in the first place, but at the neighborhood population. It was therefore essential to convey emotions and messages that the people could relate to. Self-respect and the emancipation of women were central themes for the muralists as well as for painters / graphic designers like Yolanda M. Lopéz and Ester Hernández. “Activism in the 70s had to do with me turning upside down the notion that the creation of monumental art was a male act. I started painting these ferocious Indian women who looked like they could devour you-in the ‘Uprising of the Mujeres’, for example”, said Judith F. Baca. [5]

It is widely overlooked that there was still another possibility. Many Caucasian female painters looked for a way to work in relation to the European history of painting. June Blum, Janet Cooling, Rebecca Davenport, Jillian Denby, Martha Edelheit, Martha Meyer Erlebacher, D.J. Hall, Audrey Flack, Eunice Golden, Shirley Gorelick, Connie Green, Cynthia Mailman, Mariann Miller, Catherine Murphy, Joan Semmel, Sylvia Sleigh, May Stevens and probably more[6] decided in the 60s to revive a language that had seemed extinct: realism. Many of them were former abstract expressionists; the return behind Modernism was a strange way of moving forward by moving back, as in a weird game of chess. The reigning modus was abandoned by using the relicts of the former kingdom that had been conquered, by ignoring the new highways and using the old overgrown streets and paths as shortcuts. But the reuse of realism wasn’t simply the learning of a dead language. In fact, it turned out to be a language that was only declared dead but gratefully embraced by the non-specialist public because it was “understandable”. [7] It was a language that consisted of enough formulas, symbols, compositional possibilities, patterns of meanings, styles and traditions to visualize complexities: from propaganda to allusions and irony, from picturing love and hate to distorted citations of the history of art that became filled with new meanings until it’s possible to say something new with the old language. Many of those acts are just as political as the murals of the Chicana artists, whether outspoken or subtler in their desire for transformation.

No wonder many of the artists located themselves in a network of cooperative galleries, feministic art magazines like “Heresies” or “Women’s Art Journal”, protest groups against the official museum politic and group projects like the “Sister Chapel”. The “feminist realists” never formed a group, though; it’s I who collects them under the roof of this label. The feminism the term “feminist realists” hints at is very diverse, but their practice has not been used at the time by their male colleagues – exceptions could be the “traditional figurative” painters like Jack Beal or Alfred Leslie who had a moralist or humanistic content rather than a feminist one, using the same kind of appropriation and reflection. Left out are realist painters like Janet Fish or Sylvia Mangold who were interested in still-life images of glasses, wooden floors and interiors. Linda Nochlin calls them “pictorial phenomenologists” and makes a distinction between realist paintings with a subject and those with a motif.

Motifs were what photorealism and the new figurative painting were interested in at the time: vacant cities with reflective shop windows; racing horses; neon ads; diners; the glossy surfaces of motorcycles, cars and metal toys. Pearlstein’s female nudes are masses in space covered with skin, shaped by the playful light (not subjects but objects, as Pearlstein himself remarks)[8]. Of course there were female photo realists like Idelle Weber (junk in the cities, vegetables) or Diane Burko (mountains) who had a trademark theme and worked in the same way as their male colleagues.

The “feminist realists” wanted communication and therefore a narrative content. They didn’t want to be objective and distant. If they paint more than life size it’s not for the sake of alienation and distancing, in which the object becomes but a pretext for the painterly surface, but to force the observer into intimacy. Photography is not the concurring medium you’re playing a trick at but a useful tool. Perspective and composition don’t claim to be objective, they show they’re designed by the artist, strange or even false, following her regard, with cut off limbs or figures, objects that seem to be positioned on moving surfaces, stylizations.

It’s a new construction of the view on people and objects we’re shown and the attempt for a new iconography.

I would like to present three of the artists.

Joan Semmel lives from 1963 to 1970 in Catholic countries (Spain, South America), where she paints and exhibits expressionistic paintings. When in 1970 she returns to New York she is shocked by the sexism of the public media. “The girlie magazines, the sexploitation all over were a shocker. (…) It wasn’t even sexual, it was just hard sell”[9]

A simple outrage, a simple reaction: I want let them spoil this pleasure for me, I will find a different form of representation. All I need is the view out of my own eyes, down my body, my lover’s body on the side. “(…) Identification and communal pleasures displace possible voyeurism, and body-as-object is not a given, but rather a question.”[10] The titles of her new paintings are “Intimacy-Autonomy” (1974) or “Me without Mirrors ”(1974).

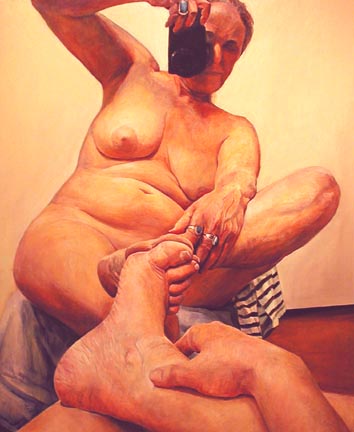

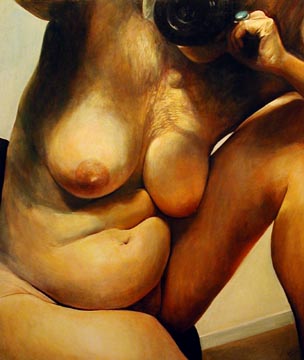

Joan Semmel

Touch, 1977

The use of photography enhances the subjectivity of the viewpoint: her breasts turn into mountains; the feet are tiny in the background. We don’t see Joan Semmel’s head because she can’t see it, and we’re seeing through her eyes. The scenery is not just a snapshot of making love, and it’s not photorealism. The backgrounds become flat, the colors move down the spectrum, towards shady greens, pale orange, lilac. Critics at the time harmlessly read these bodies as landscapes, relying on the same old ideas about the relationship between the pure joy of painting and it’s use of the body as a motif. But this is about the joy of sex. In the article “Sexual imagery in Women’s Art”, Semmel writes about herself in the third person: “Semmel’s larger-than-life depictions of the sex act fill the viewer’s visual field with richly colored flesh. She inundates us with it, making us aware of its tactility (…). She portrays the naked body, male or female, with loving attention to its gentle rhythms, swellings and concavities, as though she’s following them with her hand instead of her brush.”[11]

Joan Semmel

With Stripes, 2003

It’s a pity I couldn’t find any picture of her “fuck paintings”. Semmel invited people over to her studio to fuck, says Joanna Frueh, where a group of people would film them, draw them or make photos of the act. “Semmel would move around with her camera, looking where she wanted, seeing with her desire, creating an imagery as different from standard porn as her single female figures from conventional nudes.”[12]

Joan Semmel, Close-Up, 2001

Semmel is the perfect illustrator of the sexual liberation, convinced that “Pleasure” would eventually lead to “Insight” and from there to “Empowerment”.[13] – Empowerment for heterosexual women, mainly. There were quite a lot of female artists who turned to painting male nudes, but none who carried on the legacy of Romaine Brooks or Tamara de Lempicka. The decision to paint male nudes was an act of role reversal that was rather easy to conceive; finding new formulas for the painting of female nudes was considerably more difficult. Semmel plays a trick on the problem by calling the naked full-breasted body “ME”. That’s what I see. And now you’re seeing it, too, no matter what kind of body you’re in.

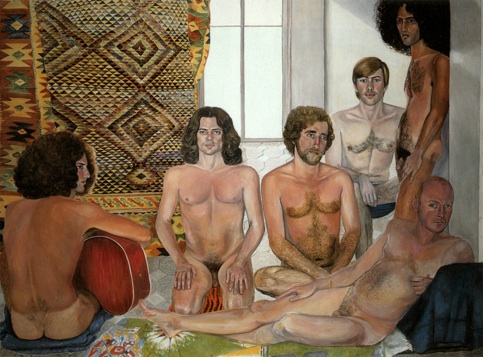

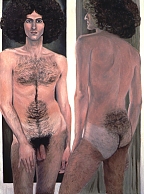

Sylvia Sleigh finds a different solution to the same problem. Rather than looking down her body, she looks to the history of painting and comes up with some only too well-known images: the painter and his model, Ingres’ pseudo-orientalist odalisque, the stylized beauty of the pre-Raphaelites’ and Botticelli’s mysterious women. She has the guts to switch the roles. The female painter’s model is male; her odalisques turn out to be nude art critics, her muses two young men with a lot of decorative hair on the head and chest to indulge in[14]. Her best-known paintings are paraphrases of Goya’s “Maja Desnuda” (“Paul Rosano reclining”, 1974), Ingres’ “Turkish Bath” (“The Turkish Bath”, 1973) and Velazquez’ “Venus and Cupido” (“Philip Golub reclining”, 1970). The role reversal is, apart from the contemporary clothing and furniture, never a simple transformation, yet even feminist critics thought she was being naive.

“When I was a young girl I thought about all the beautiful pictures of beautiful women-and there were not so many pictures of beautiful men for us-so I painted beautiful men for us!”[15] Can it really be that simple? While some consider her paintings “badly painted”, others feel the poses are “forced and uncomfortable”[16]. Sarah Kent explains this by being forced into a self-conscious voyeurism since the men, while offering themselves to be looked at, are still observing the viewer. In fact Sleigh made a point out of painting her models as personalities, creating erotic portraits.

Sylvia Sleigh

The Turkish Bath, 1973

“My idea was to do a Turkish bath which would be exactly the opposite of Ingres’ heap of flesh. Everyone in mine would be fully individualized, all would be portraits.”[17] And she adds: “You see, I hardly ever paint people until I’m rather in love with them.”[18] This “elegant and generalized eroticism”[19] is evidently not enough for Rosalind Parker and Griselda Pollock: “These contemporary men indicate relaxation, familiarity, but not sexuality. There is a radical difference between the public form of a nude reproducing simultaneously male power and male fear of difference and the individual artist’s encounter with a sitter who has agreed to pose for a portrait without his clothes on.” They come to the harsh conclusion: “Masculine dominance cannot be displaced merely by reversing traditional motifs and thinking that this automatically produces an alternative imagery”[20].

Double Image: Paul Rosano oil 1974

Only Linda Nochlin thinks poor Paul Rosano is erotic as he is lying in the grass, sunk into a reverie, oblivious to his half-opened jeans[21], exactly because of being a person and not “so void of any intelligence or energy like breasts or bottoms.”[22] What happened to Sylvia Sleigh is, according to her, nothing different than what happened to Manet in his time: the new approach has to be digested. Maybe she was right. In juxtaposing “male power” and “masculine dominance” with a solitary female artist who happens to have nice friends, R. Parker and G. Pollock overlook that the fact those friends exist show what was about to change. It’s not only the male art critic friends like Dennis Adrian, John Perrault or Laurence Alloway [23] that make the difference.

There is another, far less spectacular and reviewed part of Sleigh’s work: her portraits and group portraits of female artist friends. Cynthia Mailman is Scheherazade, Sabra Moore is Ceres. A 1977 Ceres sports a light blue blouse dotted with flowers and fish earrings. Other friends include Aphrodite, Nukua, Persephone, Isis and Artemis. They aren’t mother or earth goddesses: to see a goddess in a friend is a lovely extravaganza, not a programmatic move. The title of the pictures isn’t “Sabra Moore as Ceres” or “Ceres”, but “Sabra Moore: My Ceres”.

For the collaborative project of the “Sister Chapel”, initiated by Ilise Greenstein in 1973, she painted a Lilith. The “Sister Chapel” was a small profane temple for women by women, adorned with paintings of real or mythological heroines[24]. Twelve female painters took part; all had different approaches to the concept of a heroine, from a portrait of the politician Bella Abzug (by Alice Neel), via Superwoman (by Sharon Wybrants) to a “Self-portrait as God” (by Cynthia Mailman).

Sleigh emigrated from England to New York in 1961. In the early 1970s she got to know artists like Nancy Spero and May Stevens, and got in contact with a network of female/feminist artists who were bound together through common issues, problems, friendships, collaborations and organizations like the “Ad Hoc Committee” and “Women in the Arts” or artist-run spaces like A.I.R. (Artists in Residence), in 1972 and SoHo 20, in 1973. Both galleries showed only female artists and received quite a lot of attention. Sleigh was one of the founding members of SoHo 20 and also showed with A.I.R. Two large corresponding group portraits show the artists involved, posing for Sleigh as in a corporate group portrait of the Netherlands Golden Age, in front of one of Sleighs own paintings, hanging on a wall above a sofa. They look serious but not bored, and the painter indulges in their dresses’ lilac, bright red and apple green, in stripes, checks and ornaments. On one of them Sleigh included herself, as if added on an afterthought, a tiny bit too small and awry.

Frequently critics dismissed her painting style, her compositions and technique as awkward or naive. But she wasn’t going for the precision of photorealism. With her affectionate insistence on details, whether it be the decorative chest hair of her models or a pleat of cloth, ornamented backdrops, strange perspectives and glowing colors build up by several layers of fastidiously-applied glazes, I connect her as a painter rather with Bonnard or certain Renoirs than with Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She has to keep working a long time on each painting, and the invested diligence shows. She means it; her appropriation of art historical sources doesn’t build up a futile citation apparatus but fuels her own vision. Her paintings are very personal, not so much because she’s in love with her friends but in love with her paintings.

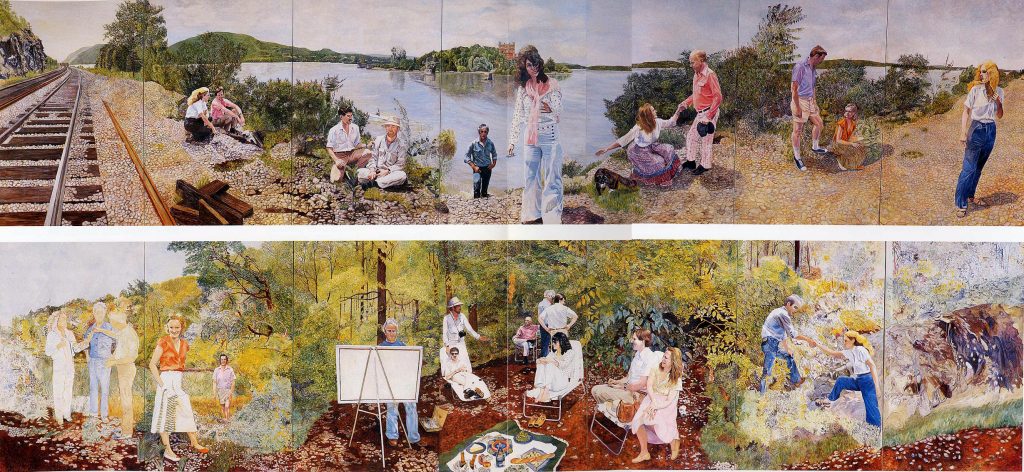

Sylvia Sleigh, Invitation to a Voyage, Invitation to a Voyage: The Hudson River at Fishkill (Riverside), 1979-99

My favorite is the huge “Invitation to a Voyage: The Hudson River at Fishkill” ( 1979-99), two panorama sights that form a pictorial room of their own, enclosing a rectangular space with two entrances. It consists of fourteen panels, one side showing a group of friends having a picnic on a small clearing in a forest, amongst them a painter with his easel; the other side a steep riverbank where man and women promenade, converse, lend each other a hand. Behind them, across the river, we make out a small island. Railways cross the picture on the left. Every stone, every leaf is there, in convincing abundance. One woman reaches out and invites you: “Why hesitate? Come with us, come to Cythera!”

Audrey Flack was the first of all photorealists, according to Louis K. Meisel. In his impressive volumes about photorealism, she is the only women artist granted a chapter[25]. Her paintings are to be found in the collections of the important New York museums and she can look back on a long list of exhibitions and publications. Since 1978 she was shown by Ivan Karp, a main promoter of photorealism, in his O.K. Harris Gallery, yet her work is still relatively obscure.

After a series of self-portraits and portraits of her daughters in the fifties, Flack started using newspaper photos as models in 1962. “She wanted to move away from the confines of her Upper West Side apartment-with the noises of Broadway buses, the neon lights of the liquor stores and cheap residence hotels flashing across the street, and the smells of the city-out into the space of the world, even when only vicariously through photojournalism. Using photographs published in magazines and pictorial albums, she scrutinized the public demeanor of political leaders as a way to understand the workings of the world: Hitler, Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill, Rockefeller, Kennedy – men who need no first names to identify them.”[26]

Public figures of women tended to belong more to the world of entertainment: Marilyn Monroe, Carroll Baker and Melina Mercouri. If the men’s gestures symbolize power, the women’s gestures are about seduction. Patricia Hills was not seduced by Flack’s rendering of them: “Flack does not seem to have the commitment to persuade us of their sexual power”[27]. But this doesn’t seem to have been Flack’s intention. The painting of Mercouri shows her at a party, laughing with tense neck muscles, for Flack the dissimulation of a “terrible pain” she empathizes with.

In 1964, while painting the picture of the Afro-American boxer Davey Moore who suddenly had dropped dead after an interview, she was thinking about “a kind of social protest realism”. Two black women cry, mourning the death of Kennedy; benign old ladies who once had been Truman’s teachers; a toothless Mexican fruit vendor; a demonstration after the murdering of Martin Luther King. All are based on newspaper photos, with the exceptions of the photos she took of a market in Oaxaca and a “War Protest March”. The painting is not photorealist in the later sense of the term; they still bare traces of her expressionist beginnings. By summarizing details and retracing the composition frame she manages to transform the snapshot of the photojournalist into a new kind of history painting. The feelings she depicts were shared or were able to be shared by many; possibly because the painted persons remain individuals and aren’t reduced to the stereotyped carriers of messages we associate with socialist realism – her aim being, after all, not so different[28]. Flack wanted to be populist, to reach broad audiences directly. “I believe that people have a deep need to understand their world and that art clarifies reality for them.”[29]

In the following years Flack seems to question herself about what popular art could mean. In 1971 she started working on a series of paintings after widely-known art historical motifs: the tower of Pisa, the copy of Michelangelo’s David or, her favorite, the Madonnas by the Spanish baroque sculptor Luisa Roldán, who are still venerated and carried around in processions. While the first pictures are still painted with brushes – very precise, but leaving out some details – she first started using an airbrush while working on the Madonnas.

All of the compositions stress the public character of her motifs – careless like a tourist photo or perfect like a postcard. The fascination with the “Dolores of Cordoba” or the “Macarena Esperanza” had for Flack had also to do with the pathos the baroque sculptor managed to bring into their faces. [30] About the “David” Flack said: “I also painted the eight hundred bricks behind him. That’s my baroque detail. I think my art has always been very baroque. I love multiplicity, curves, and detail. But David is also a symbol. It’s something everyone can relate to and I want my work to be universal.”[31]

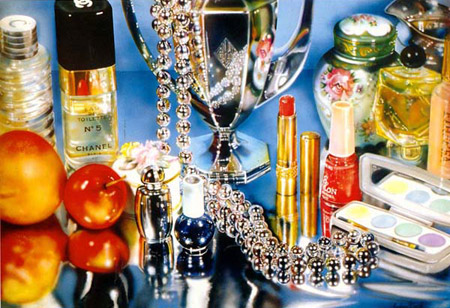

Audrey Flack

Chanel, 1974

The real baroque breakthrough occurs with her still life series started in 1972. Flack tried now to contemporalize the pictorial language of 17th century still lifes, again relating to exceptional female artists from the past: the impossibly perfect still lifes by Rachel Ruysch and a Vanitas by Maria van Oosterwycks from 1668. It’s not as Flack was the only one to paint every day objects in a distanced, scaled-up way: Idelle Weber or Ben Schonzeit make excellent examples. But Flack loads them with meanings that derive partly from the baroque iconography of Vanitas or Fortuna, partly from very private connotations. The “universal” feelings – sorrow, lust, desire, mourning about the vanity of all beauty and life and the passing luck – are mimed by her personal possessions, staged in a bourgeois hermetic interieur that doesn’t any more risk a glimpse into the outside world. The more she tries to speak for humanity in general the more she is soliloquizing, without being able to depict the reasons for her fear. They might have been an unhappy marriage and her “strangely beautiful autistic child” Melissa. The colors she sprays on the canvas, working within the colored lights of a slight projection, but otherwise “like a mule” in a dark room, are so pure and shiny as if to defy all vanity. Since 1972 Flack started using almost entirely the primary colors of red, blue and yellow, mixing all other colors by spraying those three in thin layers like in a print. The effect is that of a sophisticated pointillism, but there is also a direct connection to the glazing technique employed by the still life painters of the 17th century who helped secure them their outstanding (and lasting) brilliance and depth of colors.

Everything glitters and sparkles in Flack’s new paintings, in “Jolie Madame”(1972) or “Chanel”(1974). There are a lot of objects with a female connotation, such as make up tools, pearls, small vases and other knick-knack. The way the playing cards are laid out, the half smoked cigarettes, the watches, the perfect surfaces of impossibly fresh fruit and appetizingly shiny little cakes refer to the already half consumed life, to the possibility of catastrophes, to the vulnerability of all that just wants to keep existing in peace. The same is implicit in the compositions of those overloaded, packed images, in some kept together by the grey neutral frame she painted on the canvas to give colors the right balance. We’re mostly looking on a table crammed full with objects from a slightly elevated point of view, objects that start to push in front of one another without regard for the laws of perspective. The nail polish is seen frontally, the powder pot from above, the apples nearly fall out of the picture.

And then it’s over. Kitsch, the enlightenment, some stupid Indian Baba who teaches Flack that apples contain energy (“Energy apples”, 1980) and peaches can heal and we are all pure “light and energy”. Today she is into giant bronze godesses[32]. If all is going well and the Afro-American community stops opposing the project we will in some years be able to admire a Portuguese princess in the harbor of New York, a direct concurrence to the statue of liberty in terms of beauty and sheer height.

One shouldn’t make it easy on oneself by declaring Semmel’s attempt at making the best out of sexual imagery naive, Sleigh’s switching of gender roles and Flack’s creed in “emotions, sentimentality and nostalgia”. They reproduce the difference, which they experienced as women and women artists, but change the content. This is not an “Ecriture Feminin” but an attempt of changing the structure of visual communication from within, until it is able to express different experiences through the same old vocabulary of realist painting.

This process bore some wonderful and some pitiful results. But have a look at all the possibilities: the “Demoiselles d’Avignon” by Picasso are re-transferred into women; the three graces are black (Shirley Gorelick); I paint myself in the mirror and look as massive as a rock, deep down below my window the small metropolis (Catherine Murphy); a naked man squats in a grotto, bound by ropes that seem to adorn rather than to fetter him (Mariann Miller); even the most urban woman can become pregnant, and it looks unnatural (Alice Neel); I’m relaxing at the pool and sport a t-shirt with the image of a photorealistic painting by a colleague, spelling the letters “ART” printed on it (D. J. Hall) – and of course I’m God (Cynthia Mailman). Very seventies, isn’t it?

Translated by Antje Majewski

In: Starship, autumn 1998, p.24-35

[1] Take for example the experiences of Audrey Flack when she tried to become a member of The Club. „Machismo was a great part of the bohemian mystique.“ In: Cindy Nemser, Art Talk. Conversations with 12 Women Artists, New York 1975, S.305 ff. Consider also the diminution of women taking part in exhibitions and being reviewed in newspapers from the 30s to the 50s, in: C. Streifer-Rubinstein, American Women Artists, New York 1975, S.305 ff.

[2] As was the case for example with the flower paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, followed by those of Ruth Gray, Nancy Ellison or Buffie Johnson in the 70s. See Linda Nochlin, Some Women Realists, in: Linda Nochlin, Women, Art and Power, London 1989, S.91 ff.

[3] Judy Chicago perceived the Centre Hole first in her own “Pasadena Life Savers” (1969-70). She then met Miriam Schapiro, whose paintings like “Big Ox” could also be read as “cunt paintings”. It’s interesting that the pictures seemed to fit the concept of Michael Fried perfectly at first before the artists decided to read them in a different way in retrospect.

[4] “In spite of the catalyst role played by black and Hispanic women artists on both coasts in the early part of the 1970’s, women artists of color were not an integral part of the planning of alternative exhibitions, nor were they deeply involved in the women’s galleries (…) except as occasional members.” Judith K. Brodsky, Exhibitions, Galleries and Alternative Spaces, in: The Power of Feminist Art, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D, Garrard, New York 1994, S.118

[5] See 4), S.151

[6] Most of these artists worked in New York, and all of them in the US. Some of them I have so little information about that I can’t tell if they painted realistically mainly or only occasionally. – In my research I couldn’t find a similar approach with European female artists, with the exception of the Berlin painter Maina Miriam Munsky who specialized in scenes from hospitals (giving birth, at the gynaecologist) that juxtaposed the cold mechanical (supposedly male) world of modern medicine with the passive limbs of the treated women.

[7] “What is taste? Whose standards do we use? Who sets up these standards, and who publishes them? Why has my work upset the modernist mainstream, when the public is so overwhelmingly responsive?” – “The modernist attitude is that the public has to be educated to understand art.” Audrey Flack, On Painting, New York 1980, S.76 ff.

[8] About realists and photorealists see: Diana Crane, Art and Meaning: Themes in Representational Painting, in: The Transformation of the Avantgarde. The New York Art Worlds, 1940-1985, S.84ff. Other male artists who’s work was concerned with a (occasionally) politically motivated realism include Jeff Wall, Duane Hanson, Michael Leonhard, Franz Gertsch, John Clem Clarke, Gerhard Richter, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Equipo Chronica.

[9] In: Ellen Lubell, Joan Semmel: Interview, Womanart (Winter 1977-78): 15, S.19

[10] Joanna Frueh, The Body through women’s eyes, in: see 4), S.197

[11] Joan Semmel, April Kingsley, Sexual Imagery in Women’s Art. Women’s Art Journal Vol.1 No.1, Spring/Summer 1980, p.5

[12] See 10), p.202

[13] Semmel was an active feminist, founding member of “Heresies” and co-curator of the exhibition “Women choose women”, New York 1973.

[14] Jane Burden turned into Philip Golub, Elizabeth Sidall into Paul Rosano, Sleigh’s favourite models/muses at the time; Philip Golub being the son of Leon Golub who in his paintings is mainly dealing with Militaria, Fascism, Sadism and male violence and power relationships in general.

[15] Sylvia Sleigh in: Deborah Schwartz, An Interview with Sylvia Sleigh, Arts and Sciences, Evanstone, Illinois, Northwestern University (Spring ’78), p.12

[16] Sarah Kent, The Erotic Male Nude, in: Women’s Images of Men, ed. S. Kent and J. Morreau, p.95 ff.

[17] Sylvia Sleigh in: N. Trachtenberg, Paintings by Three American Realists: Alive Neel, Sylvia Sleigh, May Stevens, Womanart (Fall 1976)

[18] In: Making Their Mark. Women Artists move into the Mainstream, 1970-85, New York 1989, p.132 – 134. Joan Semmels is here describing Sleigh’s way of painting with nearly the same words as her own work: “Sleigh’s attention to detail in her male portraits is like that of a woman stroking her lover’s body.”

[19] “…that stays well clear of the specifically sexual”, says Dennis Adrian. More “Bonheur de vivre” than “vulgarized by the overtly erotic”. His own nude portrait by Sleigh is definitely more impressive than erotic, unless you go for the massive type, that is. Dennis Adrian, Reflection Upon Sylvia Sleigh’s “Invitation to a Voyage: The Hudson River at Fishkill”, in: S. Sleigh, Invitation to a Voyage and other Works, Milwaukee 1990, p.3

[20] R. Parker and G. Pollock, Old Mistresses. Women, Art and Ideology, London 1981, S.126

[21] In the painting “Venus and Mars: Maureen Connor and Paul Rosano” (1974), after Botticelli.

[22] Linda Nochlin, Some Women Realists, in: Women, Art and Power, London 1989, p.104-108

[23] Laurence Alloway (who was Sleigh’s husband), John Perrault (who was painted nude by Alice Neel as well), Scott Burton and Carter Ratcliff were well known art critics who posed nude for “The Turkish Bath”. “In this large painting, freely based on prototypes by Delacroix and Ingres, the wonderful pink and blond tenderness of Laurence Alloway’s recumbent form is played out against the piercing blue intelligence of his glance, and his horizontal against the swarthy, svelte, romantically aquiline verticality of the adjacent figure of Paul Rosano. In the same fashion, the richly hair-patterned torso of the dreamily relaxed John Perrault is nicely paired off with the stiffer, more frontal glabrousness of that of Scott Burton kneeling beside him, and the delights of these contrasts are set off by the richness and colouristic brilliance of the decorative patterns against or upon which they are set.” Linda Nochlin, see 22), p.106. The decorative pattern hanging by the window is a quilt that looks a lot like it was done by Joyce Kotzloff.

[24] There is a legitimate aversion against dealing with the chapter of the Goddesses in feminist history. But as I frequently found, even more outstanding “essentialists” weren’t always deadpan serious about it. – The “Sister Chapel” which originally had been planned as a complex including a library, hall of fame, museum and archive, was shown on a touring exhibition, first mounted in P.S.1, New York.

[25] Louis K. Meisel, Photorealism, New York 1980, p.241. See also Louis K. Meisel, Photorealism since 1980, New York 1993

[26] Patricia Hills, The Person, the Studio, the World: Audrey Flack in the 1960s, in: Thalia Guoma-Peterson (ed), Breaking the Rules. Audrey Flack. A Retrospective 1950 – 1990, New York 1992, p.50

[27] See above, p.55

[28] Only one image looks like plain propaganda to me: the “Sisters of the Immaculate Conception Marching for Freedom” (1965). It’s a problem of composition, of the self-assured marching of three ugly white nuns in front of a mass of black people.

[29] Audrey Flack, in: Cindy Nemser, Audrey Flack: Photorealist Rebel. Feminist Art Journal, Fall 1975: 10

[30] Flack’s “Macarena of Miracles” was shown in the Whitney Museum in 1972 and received favorable reviews; with the assumption she was camp. When Flack declared she honestly thought of the sculpture as of a masterpiece (which of course is the basis of camp: you honestly think it’s great), she and her painting looked sentimental and vulgar to many. (After: Th. Gouma-Peterson, Iconic Images for a Secularized Age: 1980-83, in: see 26), p.85. What does “camp” mean, regarding Sleigh or Flack? About Flack’s own view on the Macarena see: A. Flack, The Haunting Image of the Macarena Esperanza, in: Audrey Flack, On Painting, New York 1980, p.32 ff.

31 In: Cindy Nemser, Art Talk. Conversations with Twelve Woman Artists, New York 1975, p.312

32 Ever since the energy apples (1980) there are ugly dangles for high lights and loud, not brilliant colours. The bronze sculptures are extremely eclectic, with lots of drapes and symbols – some are Egypt, some are Indian, most of them are Greek – and the figures look like aliens disguised as “women”. And no, they are definitely not camp.